What is Lab-Based learning?

Laboratories are wonderful settings for teaching and learning science. They provide students with opportunities to think about, discuss, and solve real problems. Writing about laboratory teaching at the college level, McKeachie (1962) said:

Laboratory teaching assumes that first-hand experience in observation and manipulation of the materials of science is superior to other methods of developing understanding and appreciation. Laboratory training is also frequently used to develop skills necessary for more advanced study or research. (in Gage, p. 1144-1145)

Why use Lab-Based Learning?

Since the late 19th century, science educators have believed that laboratory instruction is essential because it provides training in observation, prompts the consideration and application of detailed and contextualized information, and cultivates students' curiosity in science. It also provides students with the opportunity to engage with science and research in ways that professionals do.

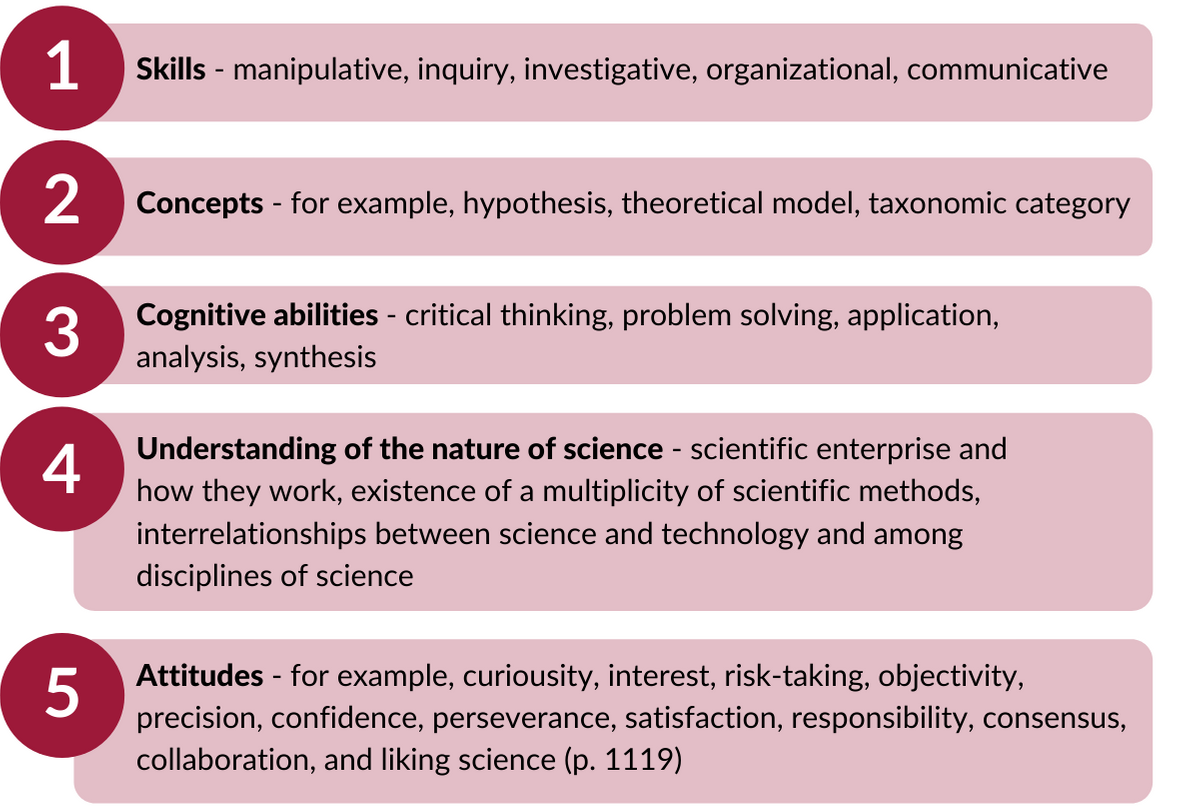

In order for labs to be effective, students need to understand not only how to do the experiment, but also why the experiment is worth doing, and what purpose it serves for improving students' understanding of concepts, relationships, or processes. Shulman and Tamir, in the Second Handbook of Research on Teaching (Travers, ed., 1973), listed five types of objectives that may be achieved through the use of lab-based learning:

Lab-Based Teaching Strategies

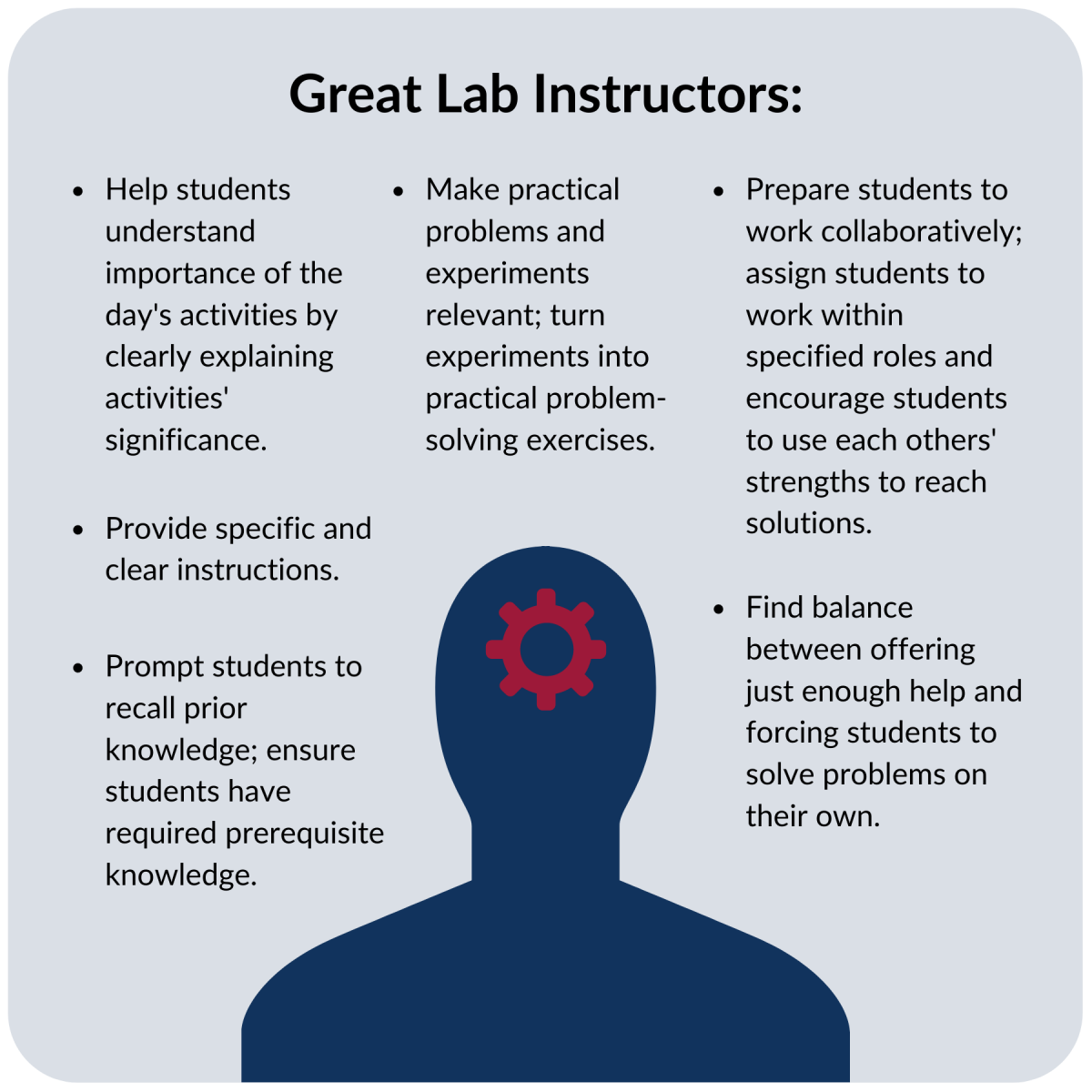

Developing and teaching an effective laboratory requires as much skill, creativity, and hard work as proposing and executing a first-rate research project.

1. Identify the goals/purposes of your lab

Before you begin to develop a laboratory program, it is important to think about its goals. Here are a number of possibilities:

- Develop intuition and deepen understanding of concepts.

- Apply concepts learned in class to new situations.

- Experience basic phenomena.

- Develop critical, quantitative thinking.

- Develop experimental and data analysis skills.

- Learn to use scientific apparatus.

- Learn to estimate statistical errors and recognize systematic errors.

- Develop reporting skills (written and oral).

Ensure that these goals are communicated clearly to students. As well, communicate success criteria to students prior to the lab and offer students the opportunity to ask questions about and clarify these expectations.

2. Prepare for your lab

Preparation, prior to the start of the semester, should include being acquainted with the storeroom of the lab so that time won’t be lost during a lab looking for necessary equipment or materials. As well, it is vital to know and share the location of the first aid kit, basic first aid rules, and procedures for getting emergency assistance.

3. Ask and answer questions strategically

Asking questions

Engaging with students helps to ensure that students are not only on track, but also feel comfortable reaching out for support if they encounter challenges in the future. Questions can be used to guide students in the right direction by prompting them to reflect on their progress, the direction they are headed in, and to consider the implications of their findings both for their immediate academic writing and for real-world contexts. Examples of such leading questions include:

- What are you currently working on? How is it going?

- This looks good. What are you going to do next?

- Why do you think that happened?

- What sort of thing did you take notes on?

- Have you thought about how you will write up this project/experiment?

- Were the results expected or unexpected? How so?

- Other people have said such-and-such. Do you agree?

- How do you think this fits in with the rest of the course?

Answering questions

No matter how long you teach or how thoroughly you prepare, there will always be questions that take you by surprise. Below are three approaches to answering questions:

- Encourage the student to figure out the answer independently. Direct them to resources (e.g., textbook, sites). Ask open-ended questions that compel them toward reflecting upon the information they have and making inferences/guesses, and guide them in exploring those guesses.

- If you aren't sure about the answer, let the student know that you will find the information and provide it to them as quickly as possible. For example, "Can I think about that? I will get back to you by the end of class."

- Tackle the question with the student or have students work together to find the answer. Suggest to the student that they investigate one resource while you (or another student) investigate another. Regroup and share findings.

4. Reflect on and evaluate your lab

As the lab section draws to a close, assess your success as well as that of your students in the lab. Ask students how they experienced the lab (e.g., highlights, challenges, takeaways) and note any feedback that can inform and improve future labs.

Helpful Resources

Articles and Reports

Gopal, T., Herron, S. S., Mohn, R. S., Hartsell, T., Jawor, J. M., & Blickenstaff, J. S. (2010). Effect of an interactive web-based instruction in the performance of undergraduate anatomy and physiology lab students. Computers & Education, 55, 500-512.

Teaching Laboratory Classes, Vanderbilt University

Websites

Teaching in Labs, University of Washington

Teaching in Labs, University of Auckland includes (with videos):

- Best Practices for Grading Laboratory Reports

- Sample Laboratory Report Rubrics