Ask half a dozen current students why Queen’s celebrates University Day and, after a few blank stares, you’ll likely receive six different answers. Of those, it’s a pretty safe bet that none will include the words “royal charter.”

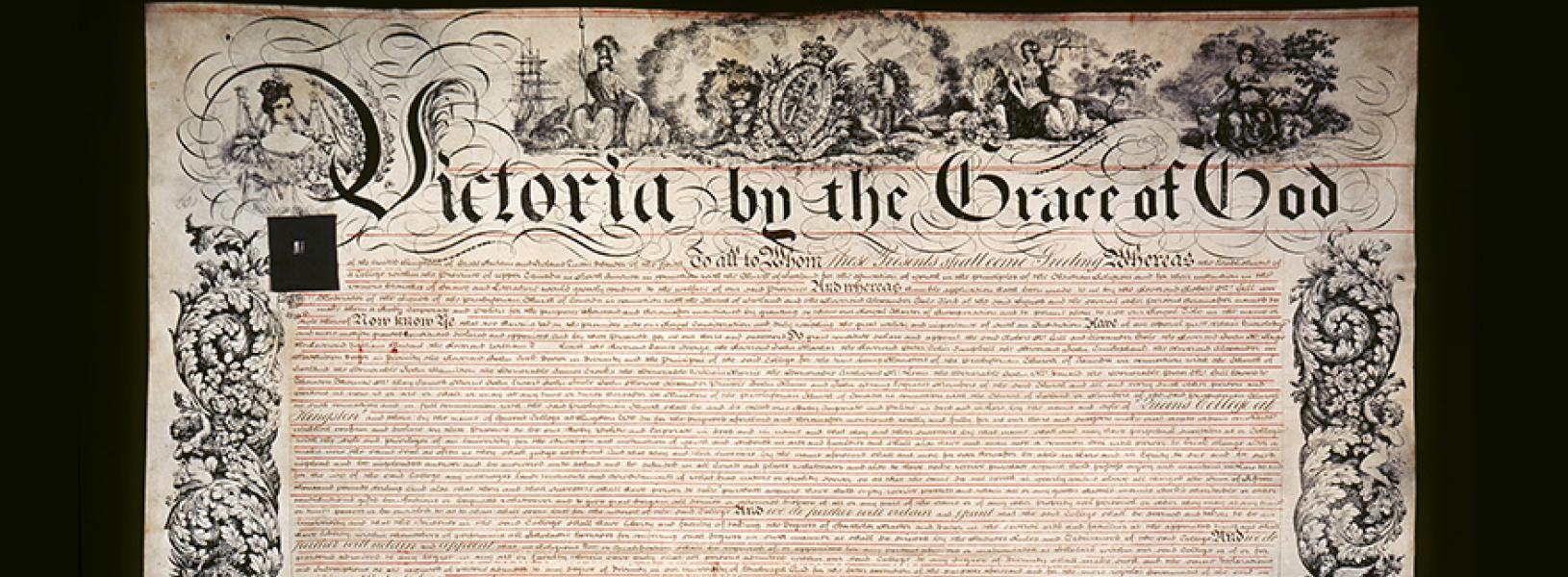

(Hint to our readers: University Day, October 16, marks the date in 1841 when Queen’s College at Kingston was incorporated by a royal charter issued by Queen Victoria.)

When I recently checked out the replica charter on permanent display in the JDUC's Upper Ceilidh, I had to ask the young woman perched beneath it to shift her laptop so I could squeeze in beside her to read the lettering. She politely complied, but showed not a whit of interest in the historic document directly above her head. Like the ceilidh’s well-worn chairs and coffee tables, it was part of the furniture and therefore invisible.

Yet without that document, the prized Queen’s degree for which she was working so hard would not exist, and she might instead be studying – perish the thought! – at the former King’s College,

now University of Toronto, 260 km up the road.

A charter challenge

At the other end of the spectrum from my accommodating view-blocker, Queen’s conservator Margaret Bignell is intimately familiar with the university’s charter. You might say she’s had a hands-on relationship with it.

A graduate of Queen’sMaster of Art Conservation program, Ms. Bignell returned to her alma mater in 1986 to ply her restorative skills in the University Archives. Three years later, she and fellow conservator Thea Burns, also a graduate of the unique master’s program, were presented with an intriguing project. They were asked to conserve the institution’s royal charter – three large sheets of creased and contracted parchment plus a badly deteriorated wax-resin seal.

With the university‘s 150th anniversary looming on the horizon, the sesquicentennial committee chaired by Professor Stuart Vandewater (Anesthesiology) was eager to resurrect the pivotal document that had ushered Queen’s into existence. Unfortunately, the charter had not aged well. “When we first saw the seal, especially, broken in pieces and with the images of Victoria almost unrecognizable, it definitely posed a challenge,” Ms. Bignell says. “For such a treasure of the university, it was a bit of a mystery how the charter had become so badly damaged.”

Signed, sealed, and delivered

The circuitous journey that brought this decrepit document into Queen’s conservators’ care began a century and a half earlier, and an ocean away, in the heart of Victorian London. Hired by a group of colonial clerics and politicians from Upper Canada, an agent had lobbied for almost a year to have Queen Victoria bestow her blessing on their proposed new institute of higher learning.

After lengthy negotiation and spiralling costs, the royal charter for Queen’s College at Kingston was duly granted and signed on behalf of Victoria by Leonard Edmunds, Clerk of Commissioner of

Patents. (As a side note, Edmunds was forced to resign two decades later, when investigations revealed he had been skimming money from fees for charters and patents. This may account for the then-astronomical fee of close to £700 charged to Queen’s – far surpassing that paid in 1827 by Anglican Bishop John Strachan’s group for a similar charter that created King’s College at York, later to become the U of T.)

When Queen’s first principal, a Presbyterian minister from Edinburgh named Thomas Liddell, crossed the Atlantic in December 1841 to assume his new position, he carried the school’s expensive document in his luggage. The parchment sheets were rolled together with ribbons in one section of an oblong tin container called a “banjo box,” while the large round seal, attached to the papers by cord, was stored separately in its own compartment or “skippet.”

Principal Liddell later complained in a letter that, while his employers had diligently insured the charter for this voyage, they had neglected to insure him!

An offer she couldn’t refuse

Waiting anxiously in Kingston, for both their principal and his precious cargo, was the nascent institution’s Board of Trustees, chaired by William Morris, businessman and staunch supporter of the Church of Scotland. The group was determined to provide a Presbyterian alternative to the Anglican-dominated King’s College, but had recently expanded its original vision of training Presbyterian ministers to include instruction in the arts and sciences as well.

To become incorporated, however, they needed official recognition from the governing body of the land. “When the Upper Canada legislature sent the group’s documentation to England to be vetted, it was deemed illegitimate,” notes Queen’s Archivist Paul Banfield. “Everything came to a grinding halt until they turned to the example of John Strachan in the 1820s, who had been able to establish King’s College with the help of a royal charter.”

The board felt the name “Queen’s” would not only distinguish them from their rivals to the west, but would also find favour with Victoria, who had assumed the throne just four years earlier. “They wanted to be as closely associated with the monarch as possible,” says Mr. Banfield. The plan worked; Victoria granted their request.

Help from a future PM

Although his name doesn’t appear on the charter, one of the prime movers – literally – of the Kingston initiative was an up-and-coming lawyer named John A. Macdonald. At a December 1839

meeting in St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, the 24-year-old Macdonald rose nervously from his seat to move the resolution for “a proposed college to be erected in this town.” Instead of the eloquent oration he’d prepared, however, the future Canadian prime minister was rendered speechless and handed his papers to the meeting’s chairman.

Sir John is nevertheless credited for either moving or seconding several motions in favour of establishing Queen’s, and, according to Paul Banfield, may also be the main reason it is located in Kingston. “The original meeting that decided a Presbyterian college should be established took place in Montreal,” says the archivist. “Macdonald is reputed to have pushed very hard for the next meeting to be held in his hometown.”

Two years later, when Principal Liddell was crossing the Atlantic with the cherished charter, that town had suddenly morphed from a military outpost to the first capital of the new Province of Canada.

The birth of a university

“Kingston was an exciting place to be in 1841,” says public historian Arthur Milnes, a fellow of the School of Policy Studies. “Not only had it just been appointed the new national capital, but the future founding prime minister of the country was establishing his political roots there. While he later went on to build the country, at that time Macdonald played an important role in building a university!”

Following the arrival of the charter, and in the first years of Queen’s existence, Macdonald continued to assist the fledgling college. He undertook legal work and guided land acquisitions for the Board of Trustees; donated books to the school library (located in St. Andrew’s Church tower); and helped negotiate the creation of Queen’s medical faculty.

Although Kingston lost the capital after only three years, precipitating an economic depression, the early 1840s had been an exhilarating period of expansion and unprecedented growth. “It was also a crucial time in the development of Canada – and much of this happened on what is now Queen’s campus,” says Mr. Milnes, noting that Summerhill had been used as a residence and meeting space for members of the new parliament. And in those heady days leading up to Confederation, Queen’s College at Kingston was born.

A charred charter?

The tightly rolled document and cracked seal in their banjo box, before conservation. (Credit: Queen's University Archives)

A century and a half later, university conservators Margaret Bignell and Thea Burns contemplated the sorry state of the royal charter as they undertook to conserve it for the upcoming sesquicentennial celebrations. Because Victoria’s great-great-great-grandson, Prince Charles, had accepted the university’s invitation to receive an honorary doctorate at convocation, the Archives staff were also tasked with creating a replica charter and seal for the prince to unveil.

The mystery of how the charter – and especially the seal – had fallen into such disrepair may never be resolved. Initially stored in the vault of the university’s bank (where it was listed as an asset in the account ledgers until 1909), the charter was moved at some point to Douglas Library’s “Treasure Room,” a repository of rare books and artifacts, and finally, in 1981, to the University

Archives’ new home in Kathleen Ryan Hall.

Ms. Bignell speculates that the banjo box in which the document resided may have been stored in the library of Old Meds when that building was damaged by fire in 1924. The lacquered metal container would have protected the charter’s parchment sheets, but extreme heat could have cracked the seal and blurred the bas-relief images of Queen Victoria that adorn both sides. As well, each time the box was picked up by its handle, the seal would have rubbed against the unlined metal wall of the skippet. Add to this a lack of humidity and temperature controls in its many different storage locations, and the result was deterioration of both the delicate parchment and the wax-resin seal.

Repair and replication

To stabilize the three charter pages, Ms. Bignell and Ms. Burns first cleaned, then gradually “relaxed” them in an enclosed humidity chamber in the Art Conservation lab, until they could be safely unrolled. Next, the parchment sheets were delicately stretched back into their original configuration on a tensioning frame. Archives staff also constructed a new storage container with acid-free board, which allows the document to be stored flat in a map cabinet drawer.

Since the ribbons were badly deteriorated, the conservators decided not to line and reuse them. Instead they gently humidified, flattened, and placed them in an envelope attached to the new storage container. New ribbons were made from a comparable seam binding.

Repairing the seal – dark green, to designate a constitutional document – presented a greater challenge. Too brittle to permit the use of pins, the five broken pieces had to be tacked in place while wax-resin infills were applied. “You can see the darker places where we mended it,” says Ms. Bignell. “Unfortunately, Victoria’s features are still quite hard to make out.”

To create a replica seal, the university applied to the Patent Office in London, which retains a complete set of moulds from every seal ever produced there. Two duplicates were ordered: one now resides in JDUC with the replica charter, while the other is kept with the original seal in the Archives.

For the charter pages themselves, Ms. Bignell took digital photos of the originals and cut them to size. “It didn’t look good on shiny resin-coated paper, so I lined it with matte Japanese paper to look more like parchment,” she explains.

The finished product was unveiled with a flourish in 1991 by HRH Prince Charles at a ceremony in the JDUC's Lower Ceilidh, and later placed in a glass-fronted wall cabinet on the second floor.

A charter worth celebrating

A replica of the original seal attached to the Queen's royal charter. (Credit: Queen's University Archives)

On Saturday, Oct. 15, 2016, Queen’s University Archives staff were in Grant Hall, welcoming back alumni for Homecoming weekend. On the Archives display table were photos of the Queen’s charter, pre- and post-conservation, and the archivists chatted with many curious visitors about the document that had helped create their alma mater. The following day, exactly 175 years after

Queen’s College at Kingston came into being, Kingston’s St. Andrew’s Church held a service of thanksgiving for Queen’s University, celebrating the original charter and the long history of Queen’s in Kingston.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Queen’s celebrated University Day – October 16 – with daylong festivities. Classes were cancelled and students celebrated with games and activities including a traditional Scottish caber toss. In 2016, the charter is certainly part of the anniversary celebrations. But the significance of a document dated Oct. 16, 1841 may not immediately resonate with many members of the Queen’s community, at least not those who daily pass by the replica in the JDUC. Perhaps, though, the fact that it is out there as “part of the furniture” says something significant about the nature of Queen’s itself.

Almost as accessible to members of the community is the original charter, safely housed in the University Archives. “People are welcome to come to our reading room any weekday and ask to see the actual charter and seal,” says Paul Banfield. “A staff member will be happy to get it out for them.”

The Queen’s royal charter, passionately lobbied for in the 1840s and painstakingly repaired in the 1990s, remains an important part of the living story of Queen’s University.

A living document

While its wording reflects both the language of the time and Queen’s origins as a Church of Scotland institution, our charter is a “living” document not set in stone, says University Secretary Lon Knox. In addition to a number of changes brought about through parliamentary amendments, from time to time Queen’s seeks the input of legal experts (most recently two retired supreme court of Canada Justices) for their interpretation of charter language.

A case in point is the curious stipulation that the college’s buildings be “no further than three miles from st. Andrew’s Presbyterian church” in downtown Kingston. This was likely intended to ensure students would comply with their written declaration to attend church regularly – and for the Scottish founders of Queen’s, there was only one choice of denomination!

Although this wording has never been amended, Queen’s obtained a legal interpretation that it didn’t limit the university’s ability to own property beyond the three-mile radius – including, of course, Herstmonceux Castle in England.

To make the charter and its multiple amendments more accessible and understandable, the Secretariat has created a consolidated version, which, though not a legal document, contains those parts which have continuing force and validity. you can read it online at queensu.ca/secretariat.

A transcription of the original charter text – containing what Mr. Knox calls “the world’s longest run-on sentences” – is also available on this site.

Advantages of a charter

Among many other distinctions, Queen’s is one of the few universities in Canada still governed by a royal charter. And that raises the question, “Why?” For an answer, the Review turned to Lon Knox, Secretary of the university. “For well over a century, Queen’s has considered itself a national university rather than a provincial or regional one. This provides our focus as we draw students from across the country,” says Mr. Knox. “So we think it fits our place in the national landscape to be governed in this unique way, where change can only be brought about through the House of Commons and the Senate of Canada.”

Unlike the U of T, Queen’s has chosen not to have its charter repealed (which would move oversight of the university to the provincial government, as stipulated in the Constitution Act of 1867). Pre-Confederation, we would have needed to petition the Queen directly for any changes to the charter, but post-Confederation, we send them to federal Parliament.

Legally, Queen’s is called a “common law corporation” because we weren’t created by an act of Parliament in either Canada or the U.K. We derive our authority directly through common law and are not registered at either the federal or provincial levels.

One advantage of our distinctive status is that we have no government appointees on our board, which helps maintain our autonomy, Mr. Knox notes. Another is that the province doesn’t have authority to make us amalgamate with another university, or to dissolve us. (They do, however, wield considerable control through financial incentives.)

In all, Queen’s has gone before Parliament nine times to petition changes to the charter, most recently in 2011. And while both the House of Commons and the Senate have accommodated all such requests to date, they are reluctant to get involved in what they perceive as provincial jurisdiction, notes Mr. Knox. “Queen’s excellent government relations work has helped us approach

parliamentarians who will sponsor our legislation,” he says. “But the last time we did so, we were told it had been a challenging process. Basically, they said they hoped they wouldn’t be seeing us again anytime soon!”

Fortunately, Mr. Knox doesn’t foresee having to return for more amendments in the near future, since he believes the charter now provides everything we need to govern the university. That said, it’s reassuring to know there is a process in place, should further tweaks be required down the road, he adds.