When Madness Comes

5th December 1998 Einstein's son had it. The daughters of James Joyce and Bertrand Russell had it. President John F. Kennedy's sister had it. Van Gogh certainly had it. All of them had schizophrenia. So do our neighbours, the children our children went to school with, the children of doctors and lawyers. So did my Aunt Evelyn, a coal miner's daughter. Some were brilliant scholars, some gifted athletes. My aunt was musical. Often they were uncannily talented at some things. Then madness came and changed everything. I count many schizophrenia sufferers among my friends, and I respect them for their strength of character. A warm smile coming out of an otherwise emotionless face reveals their great humanity. They are very sensitive individuals. For their heroic battles, they deserve a row of medals. When they themselves are improved, they feel deeply about those who are still extremely psychotic and anguished. Sometimes when they are actually the sickest person on the hospital ward, they think they are well and should not be among all these mentally ill people. The farther into an episode they get, the less insight they have. The death of a schizophrenic or harm done by a schizophrenic disturbs them deeply. After an episode, most often patients remember their bizarre actions. That is the curse of schizophrenia. Even when they are fighting not to have treatment because they have no insight into their illness, one has a sneaking admiration for their fight to do battle with the world. We find them so frustrating during such times, because we cannot even budge them from their false beliefs and mad schemes. We must remind ourselves that their minds have been hijacked by the delusions or hallucinations that are products of their disease. When I was 22, my father took me to see my Aunt Evelyn in the Warwick Mental Hospital in England. She had been there for a quarter of a century. Though he introduced me as his daughter, she believed that I was the Queen of England, and began to act accordingly. She curtsied and smiled in a conspiratorial way. Dad was not exactly amused. He looked very sad and embarrassed. He asked her if she knew who he was. He could not distract her. Suddenly, she scoffed at his silly question and called him by his childhood name, Teddy. She had been his favourite, among five sisters. Dad could never quite accept that Evelyn's husband had not been the reason for her descent into madness. There were no medications that had worked when she had her first psychotic break in 1934. Until the end she could always play the piano for the other patients, but she was seldom in touch with reality. My grandmother raised Evelyn's child. When I was a child, Dad and his sisters would descend on the mental hospital several times a year bearing hampers of food. Little was said to us children about these visits, but I could tell when it had been a bad one. Sometimes she would be in the padded cell, other times they would be allowed to see her. On such occasions, they would be amazed at how she wolfed down all the food they had brought in one go. Sometimes she would appear almost like her old self. She had one brief spell at home after her first admission, but she pulled a knife on her mother and was returned to the asylum. She would require protection forever. The street has its hazards too. Remember Andre, the Kingston man who used to walk up and down Princess Street a decade ago? His matted hair and tirades against his demons, ensured that he was someone most people avoided. A truck ran into Andre on Highway 401, killing him. It was almost certainly not a suicide, for people who have untreated schizophrenia are often tricked into thinking that they have special powers. Andre probably stepped out with his hand up, commanding the truck to stop. His fate could have been different. Andre had once been taken from the street. He responded to treatment. He was hardly recognizable, quietly reading in the library. His hair was well cut. He was clean and composed. But again, Andre slipped out of care and descended into madness. His long hair and scalp became one, glued together with a green, oozing discharge. It was not Andre, nor the truck driver, who were responsible for his death. It was his disease and an inadequate health-care system. We failed to meet his needs. When schizophrenia is in your face on the street in its untreated form, most of the public fail to recognize it, or tend to overlook those who have it, thinking of them as lazy, as drug addicts or simply as the victims of poverty. We all instinctively avoid someone who is wild and unpredictable. While chatting recently with a very nice British pediatrician outside a Toronto hotel, a person with obvious schizophrenia pan-handled a few dollars from our pockets. He probably had a family who could do nothing about his plight. The doctor was quite surprised when I said: "Another homeless person with schizophrenia." She, like many others, did not recognize the tell-tale signs of this dreadful illness. Those who have schizophrenia often live on the margins of society, even when they are relatively well. The fact is that roughly one in 100 of our fellow mortals throughout the world are afflicted with this most devastating of brain diseases. It is much more common than Huntington's disease, multiple sclerosis or Parkinson's disease, and so why is it so forgotten? Schizophrenia favours no sex, culture or social class, but once you get schizophrenia, poverty quickly sets in. But money alone does not solve the problem. I know of a sufferer who lives in his small Toyota and who has half a million dollars. I know of an extremely wealthy family who occasionally catch a glimpse of their homeless son on the corner of Yonge Street in Toronto. They are quite unable to rescue their son from his illness. The young student or professional who starts to hear voices no longer can concentrate and must often lower his or her expectations. Schizophrenia is a forgotten illness until someone is pushed in front of a subway train or a prominent sportscaster is killed because of a schizophrenic's bizarre delusions. Medical research will eventually bring a brighter future. In the meantime, those afflicted need your compassion and help. A terrible brain disease 7th December 1998 I began my psychiatric nursing training in 1961, just after the first effective psychiatric medications were introduced. The older nurses were still wondrous at the results. They had little doubt about the nature of mental illnesses. Before their eyes, broken brains started to work again. People who had been mad for years were now sane. My Aunt Evelyn was not quite so lucky. Those were the days of tea dances in the private asylums. When patients were well enough they would whirl around the great ballroom. On one occasion, I remember a fashion parade that had been arranged by Maureen, a former inpatient. Maureen was a model, and she strode down the catwalk in the Victorian ballroom with great style. Her beautiful clothes had been loaned from a posh London store. An elderly psychiatrist sitting next to me said, "You would never guess that her head was full of such terrifying delusions just eight weeks ago." I was to reflect on this in future years. We all saw the bizarre behaviour, but often only the psychiatrist and the family were privy to the secret delusions. Then there was beautiful Mary, who was a few years older than myself. She was on her way back to sanity. She was then an involuntary patient. Her first breakdown found her unkempt, withdrawn and very delusional, secluded in her London apartment. When I met her she was incredibly well-dressed and groomed, as though she feared that any sign of dirt would prolong her imprisonment in the asylum. Her efforts were heroic. On good days, she would go to occupational therapy to practice her typing. Each morning early, like Cinderella, she would polish her room. The floor would be turned into an ice rink. Then she would emerge for breakfast, dressed like Audrey Hepburn. She never spoke to other patients. She deigned to speak to me, probably because I had trained at the same hospital as her father, who was a doctor. Once, in a frenzy, she intercepted me at the railway station, begging me to aid her escape to London. Fortunately, I had no spare money. As a result of medication, Mary was soon to be on the mend. Today, Mary would almost certainly be untreated, filthy, petrified and holed up in a flat, or more likely, she would be on the streets. Without a doubt, she would have been unable to cope with today's hostels. Schizophrenia can now be treated successfully. Untreated, it creates havoc and destroys lives. The earlier that schizophrenia is treated the better the prospects. The average age of onset in all countries is about 18 for men and 24 for women. Though the illness presents itself late in an individual's development, it now seems likely that the disease has its origins in the early stages of life, probably before birth. Women have a slight advantage because of a later first psychotic break. They may have completed more education and be more mature before they have their first break with reality. But for all, the disease derails lives full of promise, and it seems to strike most often when brains are beginning to do adult work.

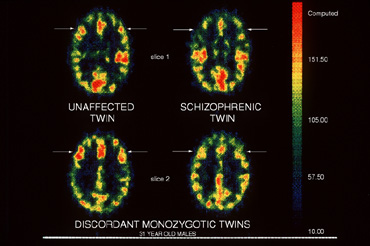

Brain scans reveal reduced frontal lobe activity in afflicted individuals. Medication seems to thrust the brain back into more normal activity. Many parts of the brain are compromised and the executive function of the brain does not quite measure up. We've all seen a person wearing Arctic clothing in the middle of the summer, or people in shirt sleeves and no socks or shoes when it's 20 degrees below. Canada is not California. Some lose limbs to frost bite. Some schizophrenics have heart attacks and don't respond to the pain. Schizophrenics are often out of touch with their bodies until they receive treatment. The person may have been a great student before things came unglued. There is much scientific evidence that there is different circuitry in the brains of affected individuals. The brain transmitters misspeak. A large sample British study of children born in 1940 found that those individuals who went on to develop schizophrenia showed some neurological differences early on in life. They were later (on average) at milestones (sitting, standing, speaking, etc.) There is a strong indication that something had gone wrong in the development of the brain in the second term of pregnancy. So often we hear people separate mind and body, but the mind is a function of the brain. A human brain weighs about a couple of pounds. A broken one is very disabling. Just because you can't see a wheelchair, do not doubt that mental illness is disabling. The government must be sensitive to the needs of the mentally ill as it implements workfare. Government forms are a nightmare even for healthy minds. Imagine how stressful they must be for those battling mental illness. Like the engine of a car, our brains can misfire. With schizophrenia, the main organ is in trouble. The only fix that can realign the brain's circuits is medication. As with Multiple Sclerosis, talk won't do it. Modern brain scans can actually show where the brain is active during an hallucination. Post mortems performed on brains of chronic schizophrenics show that there are abnormalities in various regions. In severe forms of schizophrenia there is a loss of tissue in crucial areas of the brain and the ventricles are larger. As with many illnesses, there is currently no cure, but schizophrenia can be managed.

The exact causes of schizophrenia are not yet known. A viral assault is one suspect. Certainly there seems to be a genetic pre-disposition. Often those afflicted have a family history of mental illness: an aunt, uncle or grandfather who was whispered about, did strange things, never came out of their room, hid in the attic, or died by suicide. In 1961, my peers and I were into all the latest psychiatric fads. The old nurses and doctors knew better: they were dealing with broken brains. They were often more humane. They would give sedative medicine to rest the patient from their tormenting symptoms when little else was working. Today, hospitals release, or won't admit, patients who are in torment. An American psychiatrist, on our ward in 1961, was heavily into intensive psychotherapy on very disturbed patients. With hindsight it was terrible to have let this happen. His talk therapy was like putting sophisticated software into a time-warped computer. The effect was sometimes fatal. Two patients committed suicide around that time. Soon, I would change my understanding of serious mental illness. I became a staff nurse on a neurological ward and it struck me that schizophrenia could be nothing other than a brain disease. Despite the evidence, a few professionals are still not grasping that fact. Violence

a real danger if disease not treated 8th December 1998 My Aunt Evelyn, who suffered from schizophrenia, was strangled by another inpatient at the age of 65. My dad had to identify her body. Forty years of grieving came to an end. He was deeply upset and ridden with guilt. He explained how they had tried to have her home at the beginning of her illness, but her episodes were too violent. She pulled a knife on my grandmother. They could not be both a home and a hospital. My grandmother was also caring for Evelyn's child. No doubt Evelyn, during the long course of her illness, had been violent towards patients and staff, but she was never charged for any of her assaults. Nowadays she would be. Sixty years later, she would probably be in a prison rather than a hospital. My father always felt ashamed that she had been institutionalized. I can only imagine what he would have felt if she had been in jail. One thing he knew for certain: She was mad, not bad. The public sometimes suffers as a result of a schizophrenic's preoccupations. In the United States, Theodore Kaczynski, the Unabomber, produced many victims. His family had searched for help but to no avail. When his manifesto appeared in The New York Times, his family immediately recognized it as that of their relative. They had the onerous task of leading the authorities to the Montana cabin where Kaczynski had led a solitary existence. After the trial, they turned over the reward money to help the mentally ill. Their pain continues; Kaczynski remains without insight and refuses treatment in prison. In the case of the man who shot Ottawa sportscaster Brian Smith, there was ample warning that he was a time-bomb waiting to go off. Sheila Deighton's family got help only after her mentally ill spouse shot their mentally ill son. Her husband Alistair's paranoid schizophrenia had never been diagnosed, though the family had cried out for help. I have met Alistair. He is now quite sane, as he responded well to medication. After this preventable disaster, the family now has all the help they need, but they have unfortunately lost a son. People are driven to having a mentally ill relative charged with a crime to get help. Imagine how dangerous this can be if attempting to get help by this route fails. Out of concern for the public and their loved one, families gamble on their own safety. And there is another risk: Their loved one may take off and wander the country, whereabouts unknown. Some schizophrenics get the help they need after being charged with a crime, and they usually respond well to treatment. Schizophrenics who have gone this route often end up with a stabilized illness and a much better quality of life. But help is not quick by this method. Many wait months in jail before a hospital bed can be made available. It is a myth that the seriously mentally ill are no more dangerous than the general public. Untreated schizophrenia and manic depression are often dangerous when the illness is untreated, or when the patient is in the height of an episode. In addition, schizophrenia combined with street drugs or alcohol can be explosive. Those who argue that schizophrenia is not dangerous are simply trying to reduce the stigma towards the mentally ill. In doing so, they are in cahoots with the civil libertarians who believe that you wait for a violent event before intervening. Patients do not forget what went on when they were sick. They must live with the results of their actions. Most of their violence comes out of their paranoia or from hallucinations. Families are often the victims. Yet we are beginning to hear planners talk about the concept of managing a psychosis in the home. Proper professional care must be demanded. The "home hospital" concept is ludicrous. In reality, families would be further imprisoned in their own homes. Forty per cent of schizophrenics attempt suicide at some time, and about 10 per cent succeed. One wonders whether the death certificates record: "Died as a result of untreated schizophrenia." I suspect that this is another area of silence. Talking about violence risks increasing discrimination towards the mentally ill, but not talking about violence minimizes their special needs when their illness forces them out of control. This is a classic "Catch 22." By hiding schizophrenia, we become accomplices. We make it a crime to be ill. Fads and

myths cloud understanding 9th December 1998 Schizophrenia is the same disease the world over, yet developing countries cope with it differently. I learned a lot about this at the World Psycho-Social Conference in Germany this year. In India, the family is not blamed for causing the illness. It is considered a matter of fate. The extended family system in India helps families share the burden, but as India moves rapidly towards a smaller family structure, it is feared that the mentally ill will suffer the same plight as in the West. In China, there is the problem of saving face. Much is done by barter, but shame prevents families from bartering care for their relatives. A few more privileged families manage to get relief from caregiving by bartering goods. Unlike in the West, however, China and India have not had to correct the legacies left by fads that have had such a destructive influence on Western psychiatry in the middle of this century. Terms such as the "schizophrogenic" mother (the refrigerator mother) were coined, suggesting that mothers were to blame for their children "going mad." This was a terrible period for mothers of the seriously mentally ill. It was the unkindest cut of all. This was the period in which I worked as a nurse. I remember one wretched mother visiting her daughter who was so ill she spent most of her time in the padded room. How could we be so insensitive and naive to even think that her mother would have the power to cause such a terrible illness? Freud and his colleagues added to the confusion. Although Freud never actually claimed that psychoanalysis could cure schizophrenia, psychoanalysts nevertheless got into the act. Using psychoanalysis to "handle" schizophrenia is like hitting an already wounded family with a 10-ton truck. Germany is still heavily influenced by therapy of the Jungian school. At a recent conference in Hamburg, a German whose wife had schizophrenia told me how annoyed he had been when a family new to his support group and new to the illness was referred to a Jungian analyst. The family had taken it as a good sign that their teenager had at last shown some emotion. He had burst into tears. The young man was probably totally overwhelmed by the therapy. A more destructive approach to his illness I can't imagine. Medicine and gentle encouragement was what were needed. Though most doctors have accepted intellectually that schizophrenia is indeed a brain disease, old ideas die hard. Fingers are still pointed at families. How else can one explain why physicians fail to serve patients in an emergency? Where else in medicine do you hear the words "family therapy?" The family's members are not ill. They are simply in need of information. With diabetes, it would instead be more appropriately termed: "family education." To make matters worse, we have had medical people such as Dr. Thomas Szasz, who has had much influence for decades, claiming that mental illness does not exist. Another confused physician, Dr. R.D Laing, insisted that schizophrenia was simply a healthy reaction to a mad world. Despite their profoundly dangerous views, they were both guest speakers at Queen's University. Szasz, now an elderly man, was invited by the medical students four years ago. A huge crowd turned out to hear him. Szasz must have made millions out of his book The Myth of Mental Illness. I myself bought a copy in 1962. In 1994, I challenged Szasz as he played word games with a somewhat captive, but supposedly open-minded, university audience. A student yelled at me: "Sit down lady. Do you have a problem?" There was a big problem. I was utterly dismayed that Szasz held such sway with the crowd, given that the verdict on schizophrenia was clearly in. Medical science has shown that schizophrenia is a brain disease. Szasz holds that schizophrenics really know what they are doing and that they are simply acting. He views them as deviant and believes that they should have liberty until they engage in criminal activity, and then they must be punished. But prison, of course, does not make them well. He refuses to acknowledge that flawed biology is the culprit. Perhaps the most painful moment for families during the lecture was when Szasz ridiculed a fraternal twin whose brother was very ill with schizophrenia by arrogantly employing more word games. A junior member of the Department of Psychiatry challenged Szasz, only to receive the same treatment. Dr. R.D. Laing came to Queen's around 1980 to explain how schizophrenia was really an adaptive process in reaction to a perplexing world. He packed Grant Hall, whereupon he railed against the mad world. He appeared flushed by his own success. A classic case of denial perhaps: Laing had a child suffering from schizophrenia. In the West, we have easier access to the tools for treating mental illness, yet we have more impediments to treatment: quackery, the libertarian influence, the present Mental Health Act, inadequate follow-up care, too few psychiatrists tending the seriously mentally ill, and a critical reduction in properly trained professionals. 10th December 1998 There is relief from anguish in action. But what is a family to do when there is so much silence surrounding schizophrenia? It is often a year or more into the illness before a family seeks help. Sometimes the doctor won't give a diagnosis and often won't allow the family to give information. Families almost always bear most of the responsibility, but are given little information. Some families have been scolded about using the word "schizophrenia." "Don't you go putting labels on your relative," say some doctors. How can families possibly gain access to honest help with such attitudes? Would a physician say to families, "Don't use the word 'diabetes'?" Families need to know what they are dealing with. Most of the families that seek help from the Schizophrenia Society have nowhere else to turn. They need help fast. Many have already tried other avenues. Some feel that they are at their wit's end. But as families care the most for their loved one, with support they can move mountains. Many families have been deeply hurt by professional health-care workers, and valuable time is lost when families are directed towards the wrong kind of help. Despite the hurdles, few families give up the struggle to get help. Families are often surprised when they find themselves among very normal families coping with the same illness and its bizarre symptoms. In general, the higher the professional status of the family, the slower they are to reach out for help. This is a pity because these families have more clout, but they may also have more to lose. Some families stay in denial longer and try to rationalize the behaviour of their ill relative. Families often feel guilt for their relative's condition. Families with money can sometimes hide schizophrenia longer. A case in point was Rosemary Kennedy, President John F. Kennedy's sister. After Rosemary's lobotomy for her mental illness, her family rallied to the cause of mental retardation (not to that of schizophrenia). But high-profile families seldom hide when they have dealt with schizophrenia before. They get help fast. But all families are faced with same symptoms of the disease. The rich can, of course, purchase the very best medicines, if they can access a well-informed doctor. There are some excellent physicians working with the seriously mentally ill, but they are all too few. There are reasons to hide the illness. Families lose their network of friends and sometimes can't tell their extended family. There is so much pain. And yet the quicker they get everybody on board, the better it is for the patient. But there is the treatment catch:

This is a terrible Catch-22. We must stop blaming families because often they are constrained

by the sick person's wishes. They are powerless to get their relative off the street.

Inadequate mental-health legislation ties their hands. Community treatment orders that

would help patients stay on their medicine do not exist in Ontario. More public education does benefit families. Hopefully, in the future

families will not lose half their friends when they reveal that a loved one has

schizophrenia. In the past, there have been enormous drawbacks to being open about

schizophrenia. The stigma associated with schizophrenia has engulfed the whole family,

including the patient. There are other reasons for keeping quiet. Families fear their

loved one when the illness is not treated. In addition, siblings fear that they will

become ill. Sometimes they confuse the behaviour of their ill teenage brother or sister as

acting out. In particular, a twin who is not ill will be anxious about becoming ill. For

identical twins, this is a real concern. Well children of a parent who has schizophrenia

are often very traumatized. Some have actually done the parenting for their younger

siblings. Schizophrenia is the most serious of the mental illnesses.

Schizophrenics have been robbed of so much. I frequently marvel at their ability to smile

and joke on their better days when their illness is under control and their brains are

allowing them to express themselves. Schizophrenics are demanding when they are ill. We

might behave much worse in their circumstances. Unless we have schizophrenia, it is

impossible to put ourselves in their shoes. Doctors and allied healthcare workers who suggest that the family

administer tough love should be asked: "Would you?"

Remind them that the system may allow the seriously mentally ill to slip through the

ever-widening cracks, but that families will fight not to let that happen. About 15 years ago, a kind man visiting from England gave the Ontario

Friends of Schizophrenics good advice. He was completely deaf and relayed his message

using a sophisticated hearing aid. His son was working in Europe for the Common Market

when he became psychotic. He was thrown into hospital and then abruptly released with

little clothing. He then walked over the mountains in the middle of winter and was

severely frostbitten. The man said: "Don't let professionals order

you to let go. My son is alive because of my wife and me. Until professionals do what is

humane for schizophrenics, you must be there for them." Later, his son

went on to live a fairly independent life and was a contributing member of society despite

his disability. His other son, a medical doctor, told him that he must begin to educate

the professionals and that was what he then did. And so must you. Schizophrenia is

no myth. It is real. Let any family or patient show you. More and more of the mentally ill are ending up on our streets. Many families do not even know where their ill relatives are. Many schizophrenics sleep on the streets or in doorways. They have slipped through the ever-widening cracks of a poorly co-ordinated system. They receive no medical care whatsoever. This is a common occurrence in the big cities, but it also happens in Kingston. Living rough or in crowded hostels and eating poorly are sure recipes for contracting tuberculosis. Schizophrenics are often taken advantage of. They may easily be seduced into using street drugs. There are many serious public health risks for them. The Schizophrenia Society has rescued many ill people, only to see them slip out of the system again. We have seen families burn out trying to access care. A person who suffers from schizophrenia needs a lot more than a roof over his or her head. In fact, many have been given a roof over their heads but later get evicted because their untreated symptoms and bizarre behaviours make them difficult neighbours. Some have screamed all night or have pinned threatening messages to public notice boards. The ill person cannot be blamed for his or her behaviour. Some who actually have insight but are undergoing an episode have appealed to be admitted into hospital, but have been turned away. Ryandale, Kingston's home for the homeless, will not take a person who is in a state of psychosis. It is too disruptive for their other clients. It is easy to understand why they would not take those who are psychotic, but what is an untreated mentally ill person to do in winter? Crisis services in Kingston respond only to the wishes of the client. Though they will take calls from families seeking help, they are still reluctant to step in when the client is refusing help. They say it is a matter of choice. This is very strange behaviour on the part of the crisis service if it truly understands that a person can be trapped inside the symptoms of his or her illness. Only the Salvation Army will step into the breach, and its resources are limited. Persons in a diabetic crisis can be quite obstreperous and antagonistic to treatment, but it is recognized that their behaviour is a result of an insulin imbalance. The helping professions immediately step in with life-saving treatment, to prevent further deterioration. But with schizophrenia, the same principles seem not to apply. Publicly funded services that claim to serve the seriously mentally ill should be required to help in a crisis. Schizophrenics are in crisis because of a neuro-transmitter imbalance. We hear talk of two mental health acts, one mythical and one real. But, however well the present act is interpreted and implemented, it still fails to meet the needs of some of the seriously mentally ill. Many professionals blame the Mental Health Act for not being able to provide needed care for seriously mentally ill people, but the bottom line is that governments feel that they can cut hospitalization time for the seriously mentally ill by promising to redirect funding to the community. The service providers are sold a bill of goods that suggests that programs in the community will effectively replace most hospital services. Beds then are cut gradually but brutally. Ill people are forced out of hospital earlier than is good for them in order to make room for sicker people. There's another twist. Some difficult-to-handle patients are rediagnosed as suffering from behaviour disorders, even though their problem is, and has been, primarily schizophrenia, according to years of hospital notes. By rediagnosing patients in this way, health care workers can blame the victim for being awkward. Some doctors get upset when a psychotic patient fires them. They should remember that the family is always being fired and rehired. Families often receive middle-of-the-night phone calls from another province. They are asked to send money to an ill family member, but when the parent or sibling asks where the son or sister is, the son or sister is too ill, paranoid and fearful to say where he or she is. These phone calls give a glimpse of how helpless the sufferer is. Psychiatrists can avoid serving the most seriously mentally ill if they blame the lawmakers. Doctors are blaming the lawyers, while the lawyers are blaming the doctors. The family grapples for help between the two and the patient fails to get early interventions. Everyone is blaming everyone else and the families are left to put up with these meaningless squabbles. Meanwhile, the patient deteriorates because no one will take responsibility. While it is recognized as unethical to send away people who have broken limbs or are bleeding to death, those with broken brains seldom are given the same degree of respect. In 1998, it is known that schizophrenia is one of the worst medical conditions, yet time and time again, seriously mentally ill people in crisis are released from hospital emergency rooms and psychiatric wards without help. For the most part, doctors who have respect for their patients beyond their illnesses work wonders. They have empathy and take the rough with the smooth. They earn the trust of their patients. Finding the right medication takes time, knowledge and patience. Many of these doctors do not have access to hospital beds. Unfortunately, revolving-door patients never stay with the same doctor long enough to get help. Not only is it cost-effective to act promptly, it is above all a matter of ethics that seriously mentally ill people be given the health care that they need. To hide behind a bunch of excuses is not humane. (Our pets get more help.) We should recognize that schizophrenics need a lot of health care dollars up front in order to succeed against their illness. All the burden of caring should not be left to families. Family members want to be involved, but they should not have to be the case manager, the druggist, the housekeeper, the landlord and the crisis worker. Many family members continue in these demanding roles until they die. A diagnosis of schizophrenia still brings with it a lot of discrimination. So once did AIDS, epilepsy and numerous other afflictions. Cancer used to be whispered about and diabetes was never mentioned because, before insulin was discovered, this disease meant certain death. And so what is it that turns schizophrenics into such pariahs? It is fear. It is time to break the conspiracy of silence surrounding schizophrenia and give its victims a human face. Its time to make sure that those who suffer from schizophrenia have somewhere to go to get the health care that they deserve and need.

If I were to grade the Kingston system of care for the seriously mentally ill, it would get a failing grade. Some individual professionals would get an A, but the system is a mess. The major problems are quite evident when one helps a family try to gain admission for their loved one through hospital emergency departments. Some wait long hours to be seen or referred to a psychiatrist. Some are refused admission without ever having seen a psychiatrist or without information having been taken from the family. Many patients and families have told me appalling stories of what has been said to them by emergency room staff members. I believe them; I've been there. Patients in a psychotic state are not deaf: they can hear callous and glib remarks. Emergency room staff must be better trained to serve the seriously mental ill. A major psychiatric emergency is every bit as serious as a cardiac one. But broken brains seem not to count. When a family doctor refers a patient on a Form 1 under the Mental Health Act, or a family proceeds to hospital under a Justice of Peace Order, this is an emergency. The patient must be taken to hospital, either by the police or the family, for a 72-hour assessment. Sometimes it is the only chance that the family has to begin to turn the illness around. Every practising physician should witness a family proceeding under a Justice of Peace Order. It is the most agonizing thing that a family is called upon to do and, if the hospital fails the patient, it is devastating. A man I know was not admitted on the first attempt. Ten years later, a subsequent Form 1 was successful; the disease was much more chronic by then. Some doctors say they don't do Form 1 patients. That is like a surgeon saying he doesn't do sutures. The mental health system is now a disaster zone for those in the early phases of a major mental illness. New hospital buildings and services in the community are only as good as the people who work in them. Queen's University's medical school has an obligation to teach the finest skills and up-to-date knowledge about schizophrenia. Too few psychiatrists are caring for the seriously mentally ill. Psychiatrists drift off to administer to the "worried well." There has been much confusion in the past between the demands of the mental health movement and the needs of those who suffer from neurobiological diseases of the brain. For the last two decades, government reports have stated clearly that major mental illness should be the first priority. It has just not happened. Job stress, marital problems, grief and other painful traumas cannot be compared to the horrendous turmoil that is brought about by a major mental illness. Services drift towards the worried well because they are able to ask for help. Life's troubles often put us in need of support, but for the most part our troubles pass and do not require the expensive services of psychiatrists. Major mental illness does not go away by itself. It requires treatment. General hospital psychiatric wards have often failed schizophrenics abysmally. Whether schizophrenia is in a very chronic stage, or whether it is newly diagnosed, it is serious. The system does not scrimp on serving those with leukemia. It should not scrimp for those with schizophrenia. Of course, if the system avoids doing assessments and making proper diagnoses, it can delude itself that it can manage without hospitals altogether. The rush to push the mentally ill out of hospitals is already proving to be a disaster. More and more of them are ending up, by default, in our jails. When major mental illness goes untreated, there are major consequences. There must be transitional funding to develop services being placed in the community, in order not to neglect those who need hospitalization now. There is a paradox: we are making people sicker with our present policies. What is more, if we gave the care and dollars at the beginning of the illness, there would be less demand for chronic care later. Psychiatry has come a long way from the days of insulin coma treatments, exposure to extreme temperatures, lobotomies, ice picks through eye sockets, and other questionable forms of treatment (including psychoanalysis), but there is still much room for improvement. It is high time for psychiatrists to speak out together and declare what is "best practice" for the treatment for schizophrenia. It is essential that they speak out about the current problems. Heart surgeons are quick to demand cardiac "cath labs." Psychiatrists must take a leaf out of their book. Grumbling about the failures of the Mental Health Act is no substitute for action. Psychiatrists must insist on proper lengths of stay for their sick patients. If they do not immediately speak out, there will be many people who will be too chronically ill to avail themselves of better treatments in the future. The Health Services Restructuring Commission's bed proposal for Kingston (74 chronic mental illness beds, down from 225, and 35 acute care beds, down from 47) is sheer lunacy. Muddling through while more people slip through the cracks is irresponsible. With the closure of the Kingston Psychiatric Hospital, mental illness

may not continue to have its protected funding envelope from the Ministry of Health. A decade ago, a Kingston psychiatrist told the Ontario Friends of Schizophrenics: "We don't need more research. We know how to treat schizophrenia." With all due respect to the good doctor, schizophrenics deserve to have better treatments. People with other kinds of diseases can expect continual innovation. Kingston's medical school must attract basic scientists and clinicians who are interested in neurobiological research to advance the cause of schizophrenia. Not all psychiatrists must be researchers, but they must be able to deliver state-of-the-art treatments. Virtual brain slice technologists should not, however, supplant psychiatrists who have a good doctor-patient relationship. The Ontario Mental Health Act must be revised. In addition to this, the government must address the issue of community treatment orders for those who are unable to appreciate the nature of their illness and so go off their medication. Some mental health groups (well funded by governments) have used loaded words to refer to this community legislation. They say they are "leash laws," whereas the legislation would really be a lifeline. Legislators must recognize the excruciating suffering that goes with untreated major mental illness and act. The Health Services Restructuring Commission's site proposal could be a good thing for sufferersof major mental illness. As the hospital system moves onto the King Street West site in the next century, we could have the most superlative neuro-psychiatric facility in Ontario. Kingston must be in a position to innovate. New diagnostic tests will be inevitable as science unlocks the secrets of biological psychiatric disorders. In the future, it may well be possible to diagnose and treat earlier, thus avoiding the damaging effects of the psychotic breakdown. Neuropsychiatry and neurology would be the ideal first inpatient units on a new site. There is a golden opportunity to get it right for the seriously mentally ill, but will it happen? It might, if there is a serious commitment by the provincial government, by Kingston's Healthcare 2000, and by local planners. Schizophrenia could receive the finest calibre of care, on a par with other health care areas. Heart surgery and care are not done on the kitchen table. Psychiatrists must demand a suitably designed treatment facility to assist recovery. A safe, quiet environment, privacy and room to pace and run tests, will be essential. Two per cent of the population suffers from schizophrenia and manic depression. They do not have a monopoly on pain, but it is high time for them to have their fair share of the fiscal pie. REFERENCES - Ian Chovil's Story, http://www.mgl.ca/~chovil/ - Madness in the Streets: How Psychiatry and the Law Abandoned the Mentally Ill, by Rael Isaac and Virginia Armat - Surviving Schizophrenia: A Manual for Families, Consumers and Providers, by Dr. E. Fuller Torrey - Nowhere to go, by Dr. E. Fuller Torrey - Schizophrenia Society of Ontario's Family to Family Series. 549-2485 or (416) 449- 6830 - World Schizophrenia Fellowship, wsf@.inforamp.net - Sanetalk U.K., Cityside House, 40 Adler St., London E1, England - Schizophrenia Straight Talk for Families and Friends, by Maryellen Walsh - Conquering Schizophrenia: A Father, His Son, and a Medical Breakthrough, by Peter Wyden

|