Solving the world's

greatest challenges

Imagine, engage, transform.

We are driven by curiosity, commitment, and purpose.

Global impact

We are striving to solve society’s greatest challenges through our research, teaching, and community engagement.

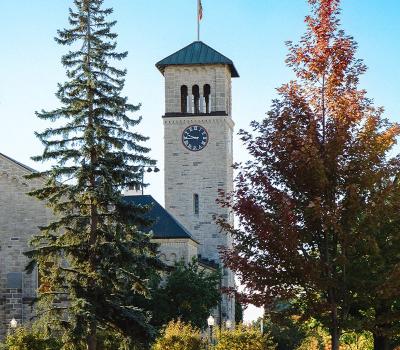

Queen's University in Canada

A better future for people and the planet is not only possible – it's our mission

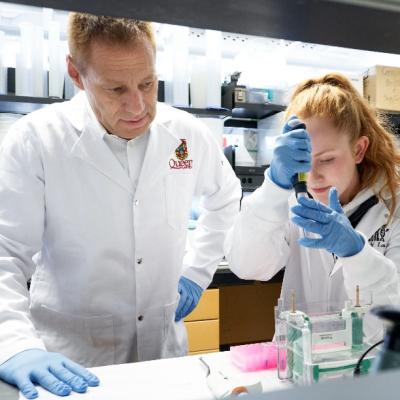

Research intensity

Our research pushes the limits of knowledge.

Global purpose

Our commitment to the common good guides our teaching, research, and outreach.

Transformative education

Our undergraduate and graduate programs and our postdoctoral fellowships set our students and researchers up to become leaders of tomorrow.

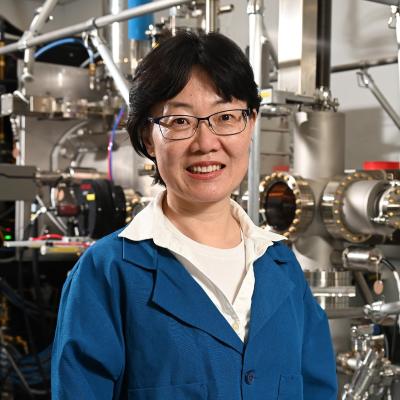

Inclusive community

Our faculty, staff, and students come to Queen’s from across the globe. Together, we learn, teach, and work in a welcoming, open, and respectful community.

Transformative education

We offer a broad selection of undergraduate and graduate programs, as well as postdoctoral fellowships. Explore and choose from more than 235 academic areas across 53 departments.

One community

We believe in diversity, equity, inclusion, and respect for all. Welcoming and supportive, Queen’s is a place to participate, thrive, and build lasting connections.

One community

We believe in diversity, equity, inclusion, and respect for all. Welcoming and supportive, Queen’s is a place to participate, thrive, and build lasting connections.