Taking Highway 6 out of Guelph toward Fergus, Ont., you’ll pass a small dairy farm that has been in the Card family since the early decades of the 19th century.

It’s flat country.

Climb up to the top of the farm silo and look south, and you can catch sight of the CN Tower. If you look closer, you might even see your future.

The oldest of five children born to Edward and Yvonne, David Card didn’t see his future mucking a barn full of Holsteins.

“I always say, if you are familiar with working on a dairy farm, all other jobs seem quite good.” He chose a different path. It seems to have worked out.

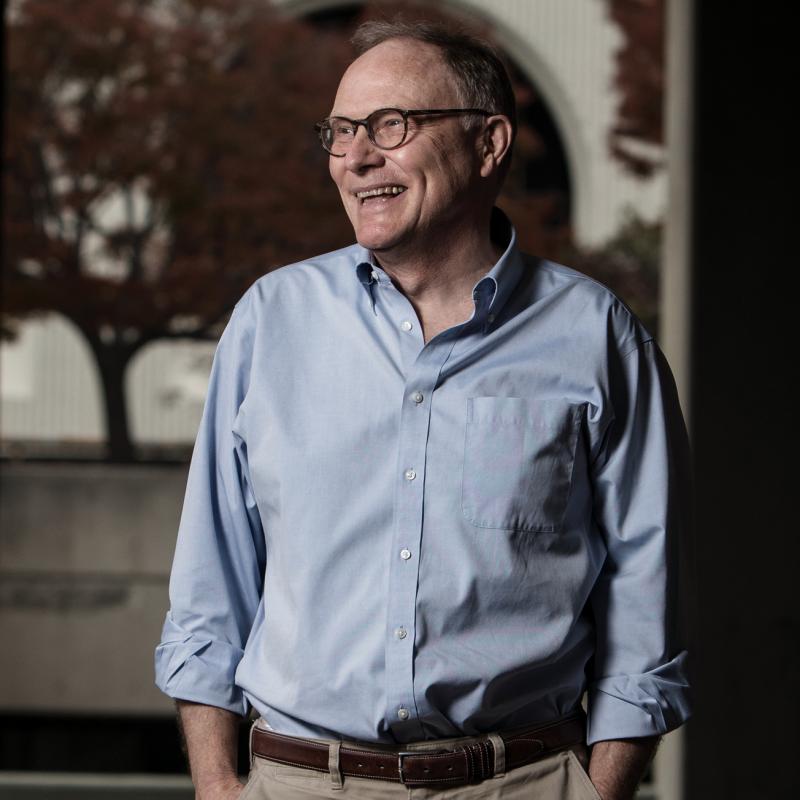

Continuing a decorated career that includes an honorary doctorate from Queen’s University and several other major awards, Dr. David Card (Artsci’78, LLD’99) is the winner of the 2021 Nobel Memorial Prize for Economic Sciences, an award he shares with Dr. Joshua D. Angrist of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Dr. Guido W. Imbens of Stanford University.

The winners’ work “provided… new insights about the labour market and [has] shown what conclusions about cause and effect can be drawn from natural experiments. Their approach has spread to other fields and revolutionized empirical research,” the Nobel Prize committee said.

With the late Alan Krueger, Dr. Card found that a 1992 minimum wage increase in the state of New Jersey did not hurt – and may have actually boosted – job growth at fast-food restaurants.

His research on immigration found that a massive influx of Cuban refugees into Miami, Fla., in 1980 had almost no impact whatsoever on the local job market.

Dr. Card’s journey to his current post as the Class of 1950 Professor of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley, made a stop at Queen’s University.

“The first time you had a course with him, you wouldn’t know him right away because he never said anything in class. It was only after class that he’d come up and ask a precisely posed question. That was when I started to notice I had a phenomenon on my hands.”

Dr. Card says, “I’m not a big believer that everyone has to talk.”

He also displayed a quick, quiet wit and a real “get-on-with-it” practical and positive demeanour, Dr. Beach says.

Both Drs. Abbott and Beach had PhDs from Princeton and felt Dr. Card was an excellent candidate for graduate studies at the prestigious university.

So, independently, they wrote glowing letters backing Dr. Card. So glowing, in fact, they were questioned by their mentor, Orley Ashenfelter, a leading American labour economist. The two stuck by their assessments.

Dr. Card excelled at Princeton and after graduation he joined the faculty at the University of Chicago, where he stayed for a year until Princeton came calling with an offer too good to refuse.

In those years, Reaganomics was still giving the free market full rein.

But in the study of labour economics, a revolution was building, led by Dr. Card, among others.

“The common term for it is the Credibility Revolution. He devised new ways of using the kind of data the world presents to us to provide more credible empirical evidence on whether there are causal relationships between certain events such as a policy change – the minimum wage for example – and the outcomes experienced by workers,” Dr. Abbott says.

He adds that Dr. Card’s genius has been to find situations in which he could apply the kind of natural experiment techniques that mimic the randomized trials conducted in medicine.

“The most important thing for successful research,” Dr. Card says, “is to compulsively try to understand what is going on at a level that is a little bit deeper than most people do in most of their lives. It’s more like taking apart a transmission. You have to take it apart and put it back together.

“You look at something and say, ‘This doesn’t make a lot of sense, how does it work?’

“I’m not necessarily trying to solve a problem; I’m more trying to figure out what’s going on when superficially something doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense.”

“The most important thing for successful research is to compulsively try to understand what is going on at a level that is a little bit deeper than most people do in most of their lives.”

He says he went to Queen’s because one of his great friends, Tim Runge (Com’78), was going. They remain close friends.

He started with physics, but “special relativity wasn’t really working for me.

“My girlfriend at the time was taking economics and I was giving her some help with some formulas. There was a famous textbook she used by Richard [Dick] Lipsey who was at Queen’s. Actually, I took a couple of courses from him.

“I started reading the text and I thought it was pretty good, so I ended up taking an economics class.”

It struck a chord.

The economics department in the mid- to late ’70s was small, with many young faculty members and a select number of talented students such as Stephen Poloz, former Bank of Canada governor. Dr. Card outshone them all, eventually winning the Prince of Wales Prize as the top student at the university in 1978.

Two of the professors he studied with remember Dr. Card as the kind of student rarely seen, if ever, in a teaching career.

Dr. Michael Abbott (now retired) was Dr. Card’s honours thesis adviser, then in his fourth year of teaching at Queen’s. He says he never had an easier supervision.

“I thought there has got to be something that’s going to go seriously wrong here.” But it never did. He realized too that “I may never be associated with a student as good as, let alone better than, David Card. I would still say that right now.”

Professor emeritus Dr. Charles Beach says he remembers telling his father – also an emeritus economics professor at McGill – that his research assistant was a rare talent. His father was skeptical, but Dr. Beach was right then and now.

Dr. Beach still has a desk plaque Dr. Card made for him at a General Motors plant in Oshawa that says “Economist at Work.”

As a student, Dr. Beach says, Dr. Card was quite modest.

This is what Dr. Card was doing when he examined the impacts of immigration and minimum wages. The results sparked a lot of outrage. Some of the attacks were vitriolic and long-lasting.

For Dr. Card, ideology is just not helpful when you are trying to truly understand something. You need to get the facts, as best you can, and present the results. What people do with that information is up to them.

“I don’t presume anybody is going to follow along. It’s not what economists would say is my advantage,” he says.

“A lot of conventional wisdom is deeply ideological. I am a bit more liberal than most people, first of all.

“[But] I think lots of times conventional wisdom is more of a religion than an understanding. It’s more a set of folk stories we tell ourselves to make ourselves feel good, especially in economics.”

Dr. Card has carried on in this vein, at Princeton and then, when his partner, Cynthia Gessele, revealed a yearning to move to California, at Berkeley.

These days, he maintains a home in town and bikes to work, not needing the plumb parking space awarded to Nobel winners. And, as much as possible, he is at a second residence in Sonoma, in wine and walnut country, where he can often be found tuning up a tractor or woodworking, a passion that started in earnest in 1990. Dr. Card takes chunks of locally grown claro walnut from trees removed from nearby groves and turns them into furniture, bowls, and other items.

He is 65 now and will likely soon find his own seat as an emeritus.

In the intervening time, he says he will tackle another of the thousands of questions in economics: understanding why immigrants to Canada turn to self-employment.

“Although a lot of people are aware immigrants are much more likely to be self-employed, it’s not clear exactly how that process works. Some who are self-employed are doing that out of desperation” while others choose self-employment “with the hope of it turning into something big. It’s hard to distinguish between them. We’ll see if we can do that.”