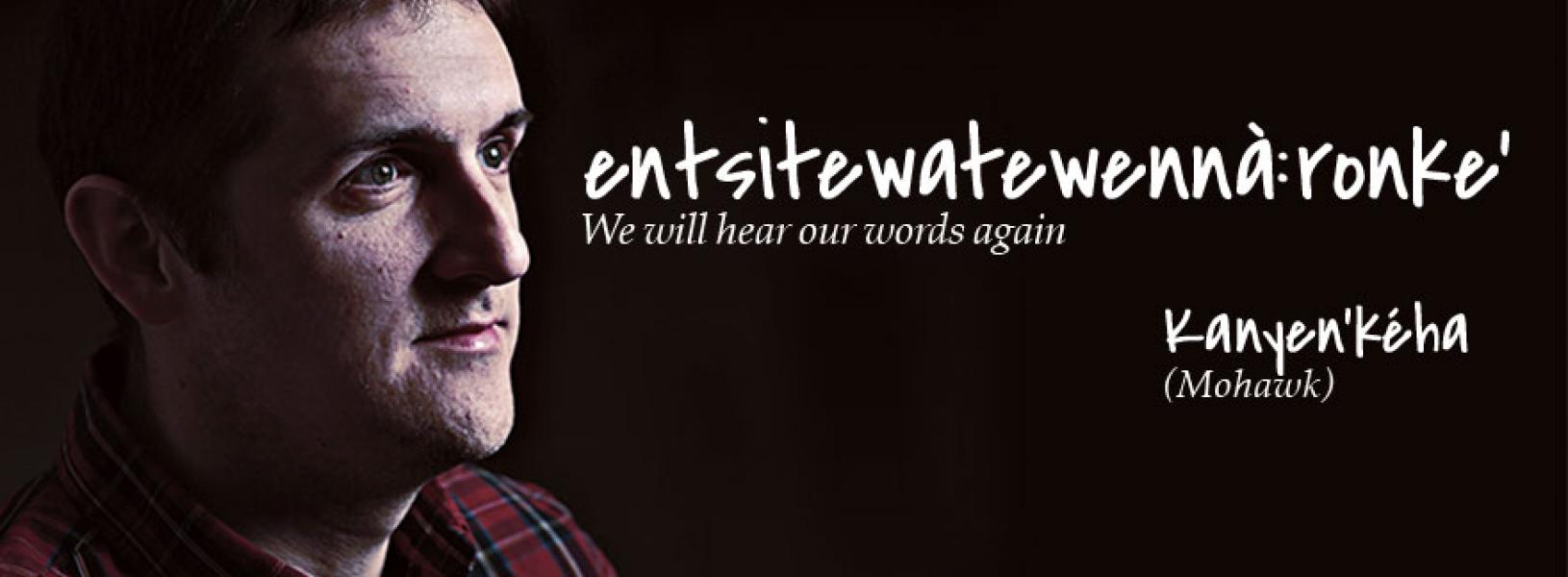

Growing up in Tyendinaga Territory, Nathan Thanyehténhas Brinklow knew a little bit of Kanyen'kéha – traditional Mohawk language – from singing hymns with his grandmother. But he wanted to learn to speak it as his great-grandparents had. He began studying the language as an adult. Today, he teaches Mohawk language and culture to students at Queen’s University's Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures.

My great-grandmother was the last one in our family to speak Mohawk. My grandmother says that the adults would speak Mohawk to each other when they didn’t want the kids to understand them… like a lot of bilingual families do!

A polysynthetic language

“Mohawk has very little in common with European languages,” says Professor Brinklow. “It can be difficult for unilingual English speakers: I encourage them to throw out everything they know about English grammar. It is a lot easier, I have found, with students who already know a second language. They know that language can work in different ways.

“Many North American languages like Mohawk are what we call ‘polysynthetic,’ meaning they are composed of complex words that incorporate many different pieces. These pieces, while they may not have any meaning by themselves when they are added to the word they give that word meaning and subtlety.

“With my students, I start by showing them the breadth of the language, while trying not to be too intimidating! I show them what the language can do. We start breaking down individual words. Every verb has a pronominal prefix – who is doing the action. And then we look at what is the action, when is the action happening, and what kind of action it is. These things are all going to form the basis of the verb. We look at how the verb changes if I am doing the action if we are doing the action if she is doing the action. Then we start changing tenses. We start with one verb root and look at all the individual things that we can adjust in that verb, and we can end up with thousands of variations!

“That brings up another problem for new students – how to use a Mohawk dictionary! You can’t just look up a word. You have to know how to take that word apart first before you can know how to use it. Memorizing whole words is useful to a certain point, for instance, when learning conjugations. But to actually get into the language, to actually be able to use it, you have to be constantly manipulating it.”

An evolving language

“The good thing about having a descriptive, polysynthetic language,” says Professor Brinklow, “is that you can create new words very easily. People have been doing it for generations: they just describe what they see. What does it do? What does it look like? What does it smell like? So, modern words are being established now, for things like ‘computer’ or ‘Internet.’

"There is no official body that defines the language, so individual people or communities come up with words. And just through the process of interaction, one phrase or another rises to the top, and enters common usage. “For ‘computer’ I would say kawennárha or, in English, ‘the words are hanging.’ If you can picture what you see on a computer screen, that’s what you see – words hanging in the air. But other people may say kayenté:ri or ‘something that knows something.’ Others still may use that word for the Internet. These words rise and fall in popularity, and eventually we come to a consensus.”