When physicians, nurses, and healthcare staff can no longer complete work due to workplace injury, patients inevitably face the consequences.

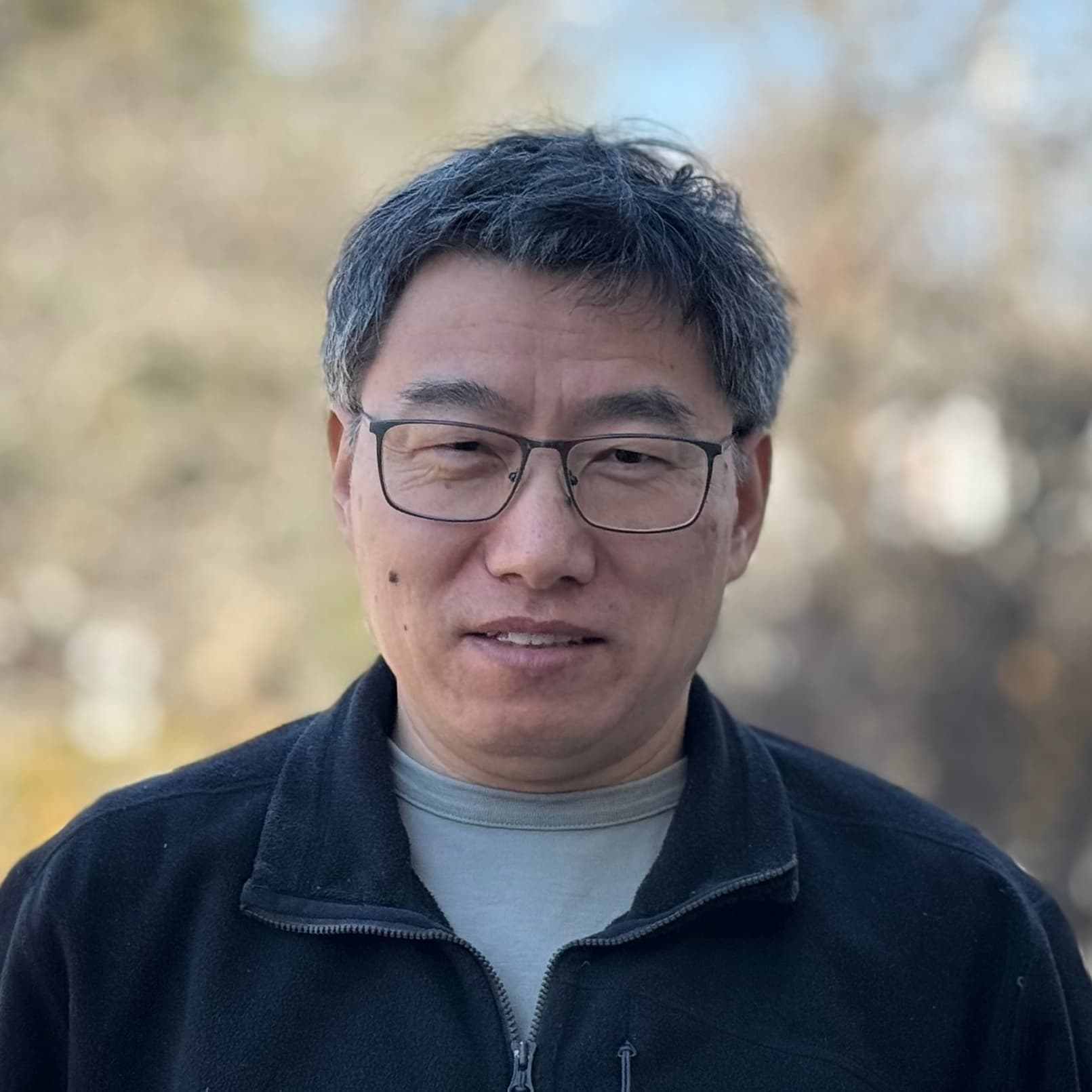

“[The Canadian] healthcare system focuses strongly on patient outcomes to treat patients better and to improve overall health. However, a lot of the time, we neglect the needs of our healthcare professionals,” says Dr. Qingguo Li, Professor in the Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering (MME) at Queen’s University.

Dr. Li leads the Bio-Mechatronics and Robotics Lab (BMRL) at Ingenuity Labs Research Institute. He is one of six inaugural recipients of the Connected Minds Seed Grant, established to support innovative pilot research projects. His awarded project ‘Exo-sensory Augmentation to Reduce Musculoskeletal Injury Risk in Clinical Settings’ aims to use innovative wearable technology to enhance sensory awareness and mitigate injury risks.

A Hidden Problem

While healthcare focuses on the treatment of Canadians, a forgotten demographic ends up being the people who provide that care: physicians, nurses, and healthcare staff themselves.

“When we come back to the literature, there are surveys that find that a very high percentage of people working in operating rooms, for instance, experience back problems and musculoskeletal injury,” says Dr. Li. The issue can lead to short careers that often result in early retirement; as Dr. Li puts it, “if the doctor is sick, who can do the treatment?”

“We focus on a group of clinicians who work in a real-time X-ray environment,” says Dr. Li. In these settings, staff wear lead aprons weighing about 15 to 25 pounds, often bending over patients for sustained periods. The combination of heavy aprons and sustained, awkward posture raises spinal loads and the chance of injury.

There are practical fixes that have been proposed but remain inadequate to address the problem. “One way is exoskeletons; however, [the surgeons] have told us that even if we develop a pretty exoskeleton, they would not use it,” explains Dr. Li. “Exoskeletons are bulky, heavy, and affect range of motion.” Another solution would be to hang a harness from the ceiling. “This would hold the weight of the load as a kind of suspension system,” he says. However, there are issues with mobility in a delicate operating environment. “[Surgeons] would need to drag the harness, and when moving in a surgery environment, that’s not a good solution.”

An Innovative Solution to a Sensory Problem

Dr. Li and his team realized that the core issue is not just physical load, but posture awareness. “This is why we propose an exo-sensory augmentation approach,” he says. “The major issue is posture.” In a demanding environment like surgery, with long procedures, the staff are deeply focused on the task at hand and do not pay attention to how their posture deteriorates. As Dr. Li explains, “the clinicians or the surgeons or the nurses are not aware [of their posture] during the operation, so if we give them this information, hopefully they can adjust their posture, stretch, and relax a bit.”

Dr. Li compares exo-sensory augmentation to the use of glasses or hearing aids — devices that amplify our senses. “Sometimes you forget about posture because you’re focusing on other tasks. So, [the system] can provide that information to you,” he explains. This approach gives staff real-time awareness of their posture as they work, allowing them to regain a sense they had temporarily lost under cognitive and physical load.

“We took a user-centered design approach by involving users in all stages of decision-making,” says Dr. Li. “We work very closely with surgeons and stakeholders. We have regular meetings with them to make solutions that are both feasible and acceptable in a clinical environment.”

The system under development has three modules to achieve overall exo-sensory augmentation: posture measurement via small wearable sensors placed on the user’s back, load estimation using biomechanical models to estimate spinal loading at different vertebral levels (e.g., C7, L4) , and feedback to the user, delivered as either haptic cues (e.g., a buzz when posture exceeds a threshold) or onscreen indicators (e.g., status on a display). These real-time cues prompt adjustments without disrupting surgery.

Designing for Accessibility

An important focus for Dr. Li is accessibility and inclusivity for all clinical roles and users. “You have nurses, surgeons, and radiology technicians,” says Dr. Li. “We are trying to develop a system that works for all of them.”

Dr. Li and his group therefore study the posture demands unique to each staff role in a clinical setting. For instance, they take into consideration that a nurse assisting a surgeon, or a technician handling X-ray equipment, face different ergonomic challenges. This consideration has underpinned the adaptability of the system to each staff member’s movement patterns and potential risks.

Dr.Li’s group also considers sex differences in how users perceive and respond to feedback. “We consider if we need to develop a universal intervention or a system with different parameters,” Dr. Li explains. By accounting for these factors early in design, the team aims to ensure the final system can support clinicians of all body types, abilities, and backgrounds.

Looking Ahead

Looking ahead, Dr. Li hopes to validate the exo-sensory system in clinical trials and to explore commercialization. “We work with Queen’s Partnerships and Innovation to get the technology to the hands of our end users, “ he explains.

Dr. Li’s long-term goal is to move beyond the lab and integrate the technology in real-time workflows. “We believe this technology can not only be applied in clinical settings or healthcare, but also in manual labour, working in a factory, for example… we believe exo-sensory augmentation can benefit the ergonomics and working conditions of other fields and make a broader impact.”