by Louisa Simmons

February 18, 2020

[Editor's note: This piece is the third instalment in our series Words of War: Canadian English in the First World War.]

Words fail our loss to tell.

Driver Reginald Frank Davey, Canadian Field Artillery, 5th September 1918 – age 25

These are the words inscribed on 25-year-old Reginald Frank Davey’s headstone nestled in the front left-hand corner of the H.A.C. Ecoust-St. Mein First World War cemetery in France. A driver with the Canadian Field Artillery, Davey voluntarily enlisted in Kingston, Ontario on November 20th, 1915. Over the next three years of war, Davey would survive a fractured tibia and fibula, a diagnosis of shell shock (contemporarily known as post-traumatic stress syndrome), and endless nights in cold, damp trenches. It was in one of these trenches when, at about 9:30 a.m. on September 5, 1918, a German shell dropped down from the bright sky above, killing Davey and six other soldiers.

Davey’s headstone is one of hundreds of thousands inscribed with a message from loved ones. When a soldier or nurse’s body was officially interred by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) in the early 1920’s, families were given the option to add a personal epitaph to the headstone. By exploring the different ways that Canadian English was used in these epitaphs to express immense personal loss, it is possible to gain insight into the sentiments and values of the broader society.

_________________________________________________________________________________

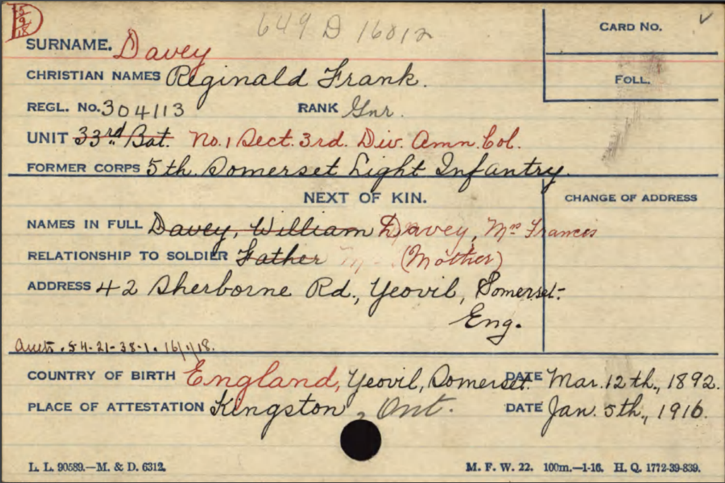

One of Reginald Davey’s enlistment documents. Photo: Library and Archives Canada

________________________________________________________________________________

The epitaphs referenced in this article were either discovered by the author during visits to the First World War cemeteries of France and Belgium or can be found in Canada’s Dream Shall be of Them: Canadian Epitaphs of the Great War by Eric McGreer or Epitaphs of the Great War by Sarah Wearne.

One of the most universal themes expressed through the epitaphs of Canadian soldiers scattered throughout CWGC cemeteries is that of the loss felt by the families left behind. Often, inscriptions were incredibly personalized, signed by “mother” or “wife & daughters.”

Death is not a barrier to love, Daddy. Kaye1

Private Peter William Lapointe MM, 2nd Battalion, 17th August 1918 – age 34

Longing to see him, to hear him say Mother.2

Private Stanley Aylett, 16th Battalion, 4th September 1916 – age 28

Our dear daddy and our hero. We miss you.3

Private George Sidney Brignell, 54th Battalion, 20th September 1918 – age 37

’Tis only those that have loved & lost can realize the bitter cost. Wife & daughters4

Sergeant Matthew Tickner, 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles, 9th April 1917 – age 43

The shell that stilled his true brave heart broke mine. Mother5

Corporal James Edward Noble, 25th Battalion, 13th June 1918 – age 21

_________________________________________________________________________________

Headstones in Wailly Orchard Cemetery. Photo: ww1cemeteries.com

_________________________________________________________________________________

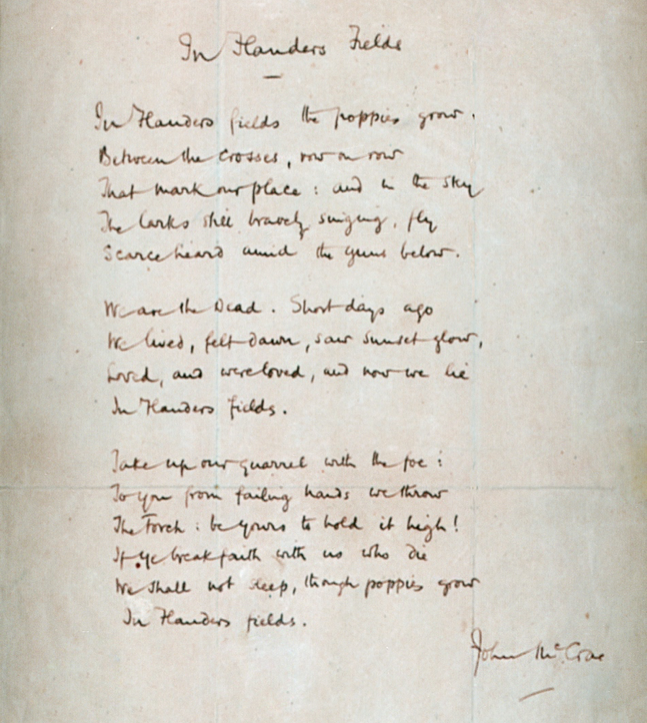

While many epitaphs were written by particular loved ones, others evoke a more general sense of loss. These often use poetic language, written either by the family members themselves or borrowed from an author whose somber words conveyed their emotions. Among others, Lieutenant Colonel John’s McCrae’s poem "In Flanders Fields", which has become emblematic of contemporary commemoration, was used in inscriptions, as it is in the first example below.

To you from failing hands we throw the torch.6

Gunner Horace Edward Walker, 72nd Battalion, 9th April 1917 – age 24

O wind if winter comes can spring be far behind?7

Captain Harry Dunlop MC, Canadian Army Medical Corps, 2nd November 1918 – age 34

How closely bravery and modesty are entwined.8

Private Francis Thomas Lind, Royal Newfoundland regiment, 1st July 1916 – age 37

His life was gentle that nature might say to all the world, this was a man. (Shakespeare)9

Lieutenant Howard Taylor, 5th Battalion, 6th June 1916 – age 21

No longer does the helmet press thy brow, oft weary with its surging thoughts of battle.10

Sergeant William McEwan, 2nd Battalion, 15th September 1916 – age 27

He cometh forth like a flower and is cut down.11

Private Frederick Wilcox, Royal Newfoundland Regiment, July 1st 1916 (age 27)

[Job 14:2]

_________________________________________________________________________________

“In Flanders Fields” written in John McCrae’s own hand. Photo: McGill Osler Library

__________________________________________________________________________________

What may strike contemporary visitors to these CWGC cemeteries today, 100 years after the war, is the number of epitaphs, such as the one for Private Wilcox above, which express loss through a distinctly Christian lens. Upon enlistment, soldiers declared their religious affiliation and, in many cases, these beliefs would have provided some comfort to soldiers in the trenches and to families mourning their dead.

Scatter Thou the people that delight in war.12

Private Reginald George Aldridge, 5th Battalion, 16th March 1918 – age 25

[Psalm 68:30]

Like Moses’ bush he mounted higher, flourished unconsumed by fire.13

Lieutenant Archie Frank Wagner, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, 9th April 1917 – age 21

[Hymn, “Peace, Doubting Heart”]

Not here – risen.14

Lieutenant Charles Henry Brown, 27th Battalion, 10th November 1917 - age 31

[cf. Matthew 28:6]

Jesus died for me. I’m not afraid to die for Him.15

Private Alexander McDonald, Canadian Machine Gun Corps, 9th September 1918 – age 21

_________________________________________________________________________________

Tyne Cot Cemetery contains the graves of 11,900 soldiers of the First World War.

Photo: Commonwealth War Grave Commission

_________________________________________________________________________________

While many of these words reflect the sense of mourning which was undoubtedly felt, it is impossible to ignore the fact that many Canadian soldiers enlisted into the war effort voluntarily. At the time, Canada was a dominion of the British Empire and the general sentiment was one of support for the British war effort. This feeling itself is reflected in the language many families used for the epitaphs of loved ones. Many honour the values of liberty and duty, while others express a deep pride in the Canadian contribution to the war.

I couldn’t die in a better cause (from his own lips).16

Lance Corporal Clayton Robertson Selkirk, 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles, 23rd June 1917 – age 21

If I fall, I shall have done something with my life worth doing.17

Private George Lawrence Holmden, 5th Battalion, 19th August 1915

Objective gained.18

Major Edward Cecil Horatio Moore, 38th Battalion, 9th April 1917 – age 40

They flung their glory to the grave that the future might be whole.19

Private William Nicol Cross, 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles, 11th June 1916 – age 23

England called, who is for liberty? Who for right? I stood forth.20

Private Sidney Howard Burgess, 10th Battalion, 9th April 1917 – age 26

My country before even you, mother dear (his parting words on leaving home).21

Lieutenant John Clarence Hanson, 104th Battalion, 17th July 1917 – age 24

Oh Canada he stood on guard for thee22

Private Reginald George Box, 16th Battalion 1st October 1918 – age 24

This sense of duty and national pride is even more evident in the epitaphs of soldiers who lied about their age in order to enlist. The minimum age of enlistment during the First World War was 18, yet there were many cases where younger boys pretended to be of age in order to serve. The epitaphs of these boys, as well as men still in their youth, express the sense of duty they felt but also the distress of parents who outlived them.

Like a soldier fell for King and country on 18th birthday.23

Private Roy Novello Riley, 13th Battalion, 8th August 1916 – age 18

Scarce boy, yet man, with torch held high, his scroll for us to die.24

Private Francis Reuben Brown, 102nd Battalion, 23rd March 1917 – age 18

Who died for his King and country at the tender age of 17.25

Private Frank Williams, 49th Battalion, 14th April 1916

Only a boy playing a man’s part, giving his life for freedom’s cause.26

Private Douglass Clark, 1st Battalion, 5th April 1917 – age 17

Our baby boy.27

Private Lionel Wellington Nutter, 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles, 25th March 1916 – age 19

These inscriptions help to humanize the statistics: In all, about 650,000 Canadians enlisted in the war effort and of those, 66,000 lost their lives and a further 172,000 were wounded. The epitaphs, chosen with care by Canadians navigating post-war society, do not simply honour deceased soldiers or give insight into the complex emotions tied to the catastrophic loss of life. They also reflect a society’s effort to find peace, understanding and identity in the shadow of war.

Gone. One of the best. No words can bring him back.28

Private Ernest Alfred Insley, 2nd Battalion, 9th April 1917 – age 19

References

Epitaphs 1-2, 4-5, 7, 9-10, 12-13, 16-18, 21, 23-24, 27-28

McGreer, Eric. 2017. Canada’s Dream Shall be of Them: Canadian Epitaphs of the Great War. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfred Laurier University Press

Epitaphs 6, 14, 22

Wearne, Sarah. 2016. Epitaphs of the Great War. London: Uniform Press.

Epitaphs 3, 8, 11, 15, 19-20, 25-26

Observed by the author in First World War cemeteries of France and Belgium