"Cold-hearted" protein protects saltwater fish from freezing

February 13, 2014

Share

By Anne Craig, Communications Officer

A team of researchers at Queen’s University led by Peter Davies has uncovered a unique protein in winter flounder called Maxi, which prevents the fish from freezing. This antifreeze protein is significantly larger than others they have studied from fish, insects, plants and microorganisms – hence the name.

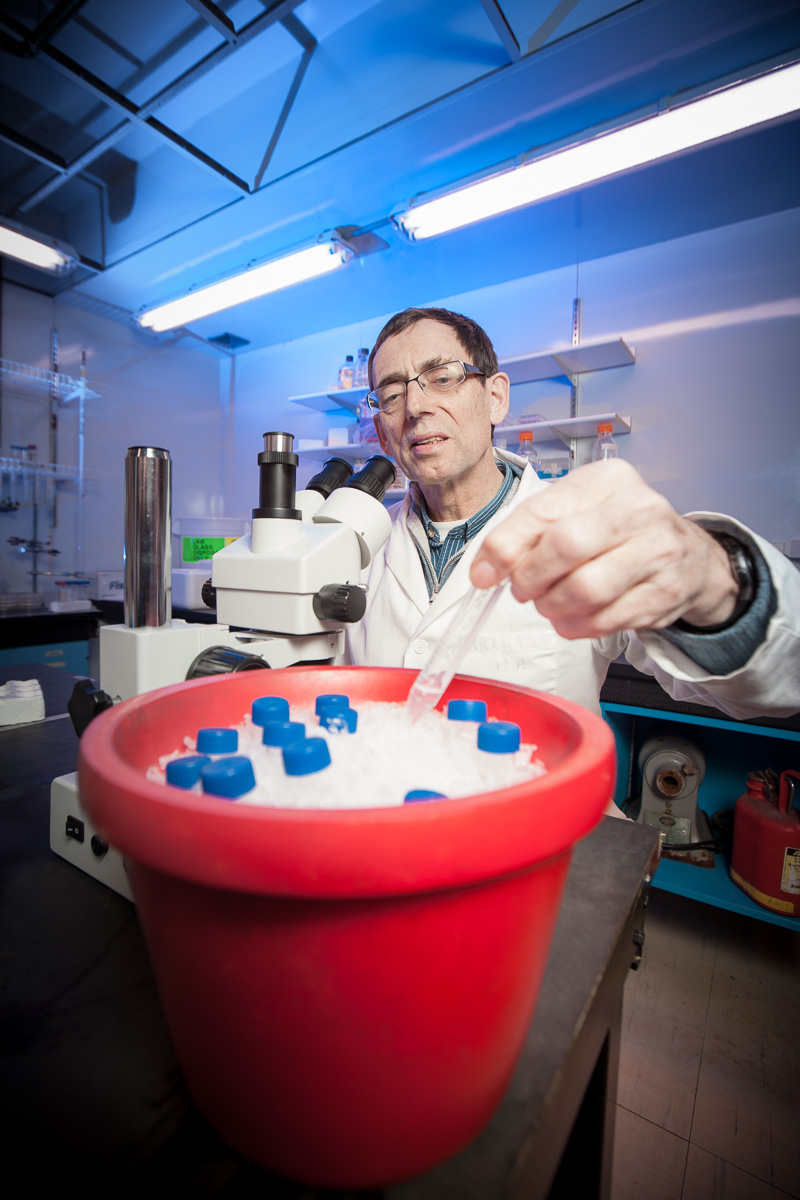

Peter Davies and his team have discovered a new protein called Maxi.

Peter Davies and his team have discovered a new protein called Maxi.Antifreeze proteins suppress the growth of harmful ice crystals in fish living in near-freezing seawater. The proteins bind to the surface of ice crystals to stop the ice from getting big enough to kill the fish. The ice-like waters in the interior of Maxi also help it bind to ice because they protrude through gaps in the protein chains and zip onto the ice, similar to what happens when you stick your tongue on a really cold Popsicle: your tongue will freeze to the ice.

“This could have implications in protein engineering for redesigning or selecting proteins to work at low temperatures,” says Dr. Davies. “A protein like Maxi could also be used to make salmon freeze-resistant for farming farther north in the Maritimes.”

A normal protein is made from a chain of amino acids that fold into a three-dimensional structure. During the folding process, water-fearing amino acids move into the middle of the protein and force the water out, while water-loving amino acids stay on the outside to help make the protein soluble. Maxi, on the other hand, uses ice-like waters on the inside of the protein to strengthen its structure.

The group’s research was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and was published today in Science.