The Conversation

Belief in touch as salvation was stronger than fear of contagion in the Italian Renaissance

July 21, 2021

Share

In 1399, a crowd gathered in the Tuscan city of Pisa, even though people understood that a plague ravaging the area was contagious. Devotees travelled from town to town and carried a crucifix — a sculpture of Jesus on the cross — which the crowd longed to touch.

Authorities tried to ban the group but had to bow to public pressure. A witness exclaimed, “Blessed is he who can touch it!” Those who could not reach the sculpture pelted it with offerings, including candles, so that these objects could touch it by proxy.

Authorities tried to ban the group but had to bow to public pressure. A witness exclaimed, “Blessed is he who can touch it!” Those who could not reach the sculpture pelted it with offerings, including candles, so that these objects could touch it by proxy.

That year, in the midst of a plague, often hundreds of people gathered and fought to touch and kiss crucifixes. The belief in touch as salvation was stronger than the fear of contagion.

As we are all too aware now, after over a year of social distancing due to COVID-19, touch was and is a much-desired privilege. In the Italian Renaissance, people longed to touch not only each other, but also religious sculptures — touch was a form of devotion.

Accessing the sacred

Renaissance Italy was home to Jews and Muslims, as well as Christians.

For Christians in the Renaissance, objects could be holy, and so touching them was a way to access the sacred. The cult of relics illustrates this. Relics are physical remains of a saint, either of the saint’s body (such as bones) or of something the saint touched.

These holy physical things are housed in reliquaries, containers to protect and display relics. In the Italian Renaissance, reliquaries took the form of naturalistic sculptures that seemed to bring the saint back to life.

Pilgrims travelled sometimes hundreds of miles on foot to reach these relics — and, for those who could afford it, buy a “contact relic,” which was made by submerging the relic in oil and then dipping a cloth into that oil. By touching that cloth, perhaps wearing it as a talisman, the believer was a part of a chain of physical contact that led to the divine.

Others touched reliquaries. A relic of St. Anastasia is embedded in a glass covered receptacle buried in the chest of a lively, blushing sculpture, so that the faithful could see it. The lucky few could reach forward and touch the jewel-like container, as the martyr would seem to look with heavily lidded eyes, almost bemused at this rather intimate gesture.

Sculptures with joints

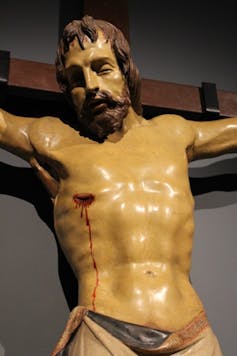

People also longed to touch sculptures that did not have relics, including life-sized crucifixes, which in the Renaissance were sculptures of a muscular Jesus, whose body is covered only by a small loincloth. Before Michelangelo, crucifixes were the public nudes in Renaissance cities. Many crucifixes hung high in churches, and Renaissance writers describe saints miraculously elevated, so that they could embrace and kiss the sculpted body of Christ.

Some sculptures have joints in the shoulders, so that at the annual commemoration of Christ’s death (on Good Friday) devotees could take part in a sacred drama, in which the figure of Christ was taken down from the cross and mourned, wrapped in a shroud and placed in a tomb.

During this re-enactment, a lucky few believers could embrace and kiss the sculpture and feel as if they had the ultimate privilege of touching Jesus’ body, reciting the prayer: “I, a sinner, am not worthy to touch you.”

In the home

Wealthy families had sculptures that they could touch at home, such as small crucifixes, which often have feet worn down by repeated touch so that the toes are barely visible.

Young women getting married or becoming nuns were given painted wooden life-sized sculptures of baby Jesus or another infant saint, which they would tend as if they were real infants, dressing them in luxurious clothing.

Meditational handbooks told women to imagine that they were fondling baby Jesus.

Anyone who could afford it would have an image of the Virgin Mary and baby Jesus in the bedroom. These sculptures place emphasis on touch, as Mary and Jesus’ limbs are gently intertwined.

But wealthy parents rarely touched their children – infants were sent away to live with a wetnurse until about the age of three, and handbooks on child rearing warned parents not to embrace their children when they returned home. So, in some cases, mothers may have touched sculptures of babies more than they touched their own children.

Interacting with sculptures

Though devotional touch was a privilege for the wealthy, practices of interacting with sculptures as if they were bodies of flesh and blood cut across social classes.

A pair of life-sized painted terracotta sculptures of the Virgin Mary and her husband Joseph watched over a stone crib at Florence’s orphanage, the Ospedale degli Innocenti. Abandoned infants were placed temporarily in the care of these sculpted parents.

The figure of Mary was sculpted only with a simple red under dress, with no cloak or veil, and so was likely dressed in fabric clothing, probably donated by a local woman. Women would have also dressed and undressed this sculpture and others like it as an act of devotion, as it would be scandalous to have a man be so intimate with a sculpture of the Virgin Mary.

Sculpted bodies inhabited cities

Sculpted bodies inhabited Renaissance cities along with living people, filling Renaissance churches, watching over the streets and gracing the bedrooms of even moderately wealthy patricians.

In a society that was ambivalent about the proprieties of touching living flesh, touching sculpted bodies could offer comfort or even salvation.

Renaissance philosophers and clergymen argued that touch was sensual and earthy and that supposedly weak-minded women and children were more in need of such physical aids in their devotions than educated men.

But ultimately, touching art was a privilege, a way of touching the divine.![]()

Una Roman D'Elia , Professor, Art History and Art Conservation, Queen's University .

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Conversation is seeking new academic contributors. Researchers wishing to write articles should contact Melinda Knox, Associate Director, Research Profile and Initiatives, at knoxm@queensu.ca.