Modelling the new coronavirus variant

January 13, 2021

Share

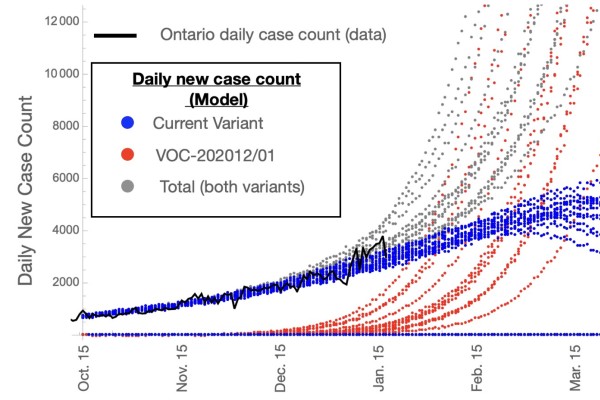

It’s been nine months since Professor of Mathematics Troy Day joined Ontario’s COVID-19 Modelling Consensus Table, and his work is now more pressing than ever. He has turned his attention to the new variant of the virus first found in the UK, and his most recent models indicate this more infectious strand of the virus could become dominant in Ontario by February.

The Gazette interviewed Dr. Day when he first joined provincial table in April, and we’ve connected with him again to discuss his latest findings.

When did the new variant of the coronavirus become a focus of your work?

Day: I started shifting my attention to the UK variant in early December, shortly before the first cases were identified in Canada.

How did you determine that the new variant could become dominant in Ontario by February?

Day: There is a great deal of uncertainty with that projection, but we took estimates from its rate of spread in the UK and applied them to the outbreak in Ontario, under different assumptions about when the first cases arrived in Canada. If the first cases entered Canada in October (which is plausible given the extent of circulation in the UK at that time) and circulated undetected until recently, then we might expect it to become dominant in February or March. On the other hand, if it first arrived in Canada in December (as another example) this date would be pushed forward by about another two months.

According to your models, what might the ramifications be if the new variant does become dominant?

Day: The most troubling projection to me is that, if everything about the spread of the variant works the same in Canada as it has in the UK, then the doubling time of the outbreak might be reduced from around 40 days to less than two weeks.

Now that you’ve been serving in this role for nine months, can you describe the value of the table and how it affects decision making in Ontario?

Day: Good question. No doubt making decisions at the governmental level is very difficult since they need to integrate all of the information they receive about the epidemiological projections with everything else (health care capacity, economic considerations, people’s willingness to adopt different behaviours, and so on). I think our table has been important in guiding the government’s response by providing the best possible information about how the outbreak is likely to unfold under different circumstances. And, despite the pandemic, it’s been really enjoyable working with such a multidisciplinary team of people from so many different institutions and agencies.

What’s next for your modelling work and for the COVID-19 Consensus Table more generally?

Day: At the moment we are engaged both in further monitoring of the spread of the UK variant and updating the projections. We have also been modeling how best to deploy sequencing capacity for tracking the variant as well as trying to develop methodology for quickly identifying any other new variants of potential concern that might arise.