New hope in Lyme disease battle

December 18, 2017

Share

Lyme disease can leave people feeling fatigued, fevered, and stiff but many don’t know it can also cause a serious heart condition known as Lyme carditis.

The condition is most prevalent in males under 40 years of age and a team of researchers led by Queen’s University cardiologist Adrian Baranchuk has now advanced a revolutionary approach that could lead to a different method to treat these patients.

The condition is most prevalent in males under 40 years of age and a team of researchers led by Queen’s University cardiologist Adrian Baranchuk has now advanced a revolutionary approach that could lead to a different method to treat these patients.

Lyme carditis specifically attacks the electrical system of the heart, leading to a rapid progression to atrioventricular block (AV) which is a complete shutting down of the heart activity. Typically the condition is treated with the installation of a permanent pacemaker but Dr. Baranchuk’s research indicates this isn’t always necessary. In all five of his test cases, the patient’s heart returned to normal after the use of antibiotics, and only some of them, have required a temporary pacemaker for few days.

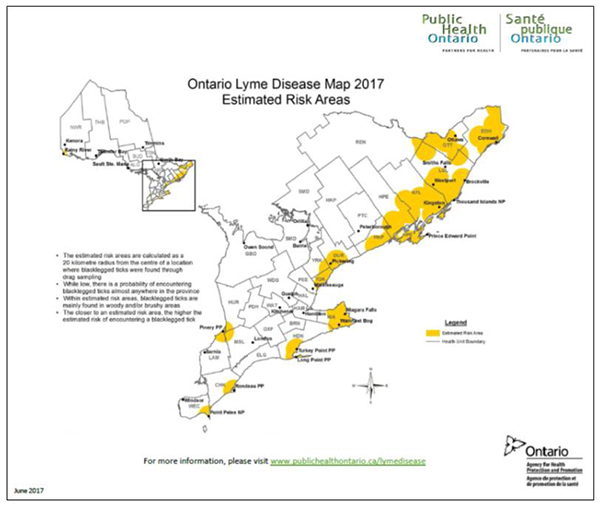

“Lyme disease is transmitted by infected ticks, primarily black-legged ticks, and Kingston is in the middle of one of the endemic regions in Canada,” says Dr. Baranchuk. “The disease become reportable in 2009 and since then, case numbers have steadily climbed. With that, the cases of Lyme carditis are also increasing.”

According to numbers provided by the Government of Canada, there were 917 cases reported in Canada in 2015.

Dr. Baranchuk credits Kingston Health Sciences Centre nurses Crystal Blakely and Pamela Branscombe with identifying the initial case of Lyme carditis, presenting this cases to Dr. Baranchuk and his team, and the team coming up with a solution that saw all five males make a full recovery.

The first case that caught their attention was a 23-year-old male who was admitted to the cardiology department with a failing heart. This came after three emergency room visits and two visits to a medical clinic. After consultation, it was decided to treat the patient with antibiotics and to insert a temporary pacemaker. His heart returned to normal in 48 hours.

“The red flag for us was his age and the fact he had no prior cardio issues,” says Ms. Blakely. “It didn’t make sense to us why he was presenting with these symptoms. We only knew he had just tested positive for Lyme disease and that’s when we starting putting everything together.”

The same was true for the next four cases Dr. Baranchuk used to test his theory. The next three cases involved males in their 30s while the fifth case featured a 14-year-old boy who was admitted to Kingston General Hospital with a second degree AV block.

“There are many risks when we implant a permanent pacemaker in a young person plus the treatment is expensive and for life,” Dr. Baranchuk says. A typical pacemaker lasts seven to 10 years. In a young person, they may need the pacemaker replaced more than six times in their lifetime which involves surgery that it is not complication-free. This new approach could solve that problem.

Moving forward, Dr. Baranchuk and his team are working to track Lyme carditis cases from across Canada to continue moving his research forward.

“We need to educate health care professionals about Lyme carditis and its treatment,” he explains. “I would also like to apply for funding for a multi-centre study into Lyme disease and Lyme carditis. There is a better way to treat this and medical professionals aren’t always prepared. We can change the treatment approach for this disease.”