New hope for prostate cancer patients

November 14, 2014

Share

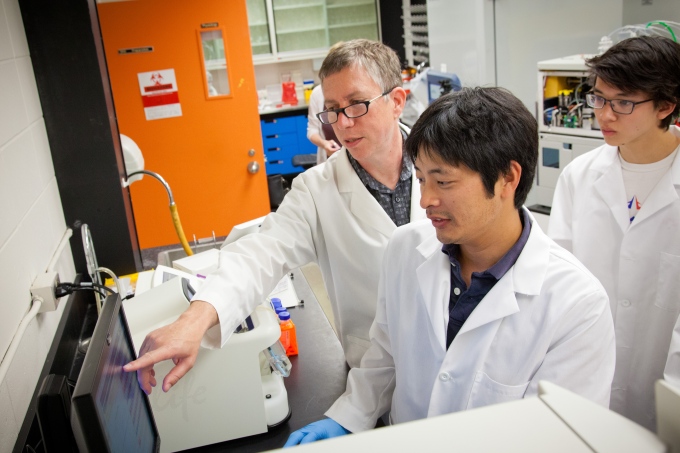

Queen’s University pathologist David Berman plays a critical, if little-seen, role in a patient’s journey from medical consultation to disease diagnosis.

“I’m the one who looks at the patient’s tissues under a microscope and determines, this is benign, this is malignant,” he says. “And if it’s malignant, I help answer important questions such as: does it need treatment and, if so, what kind? Or can this be left alone?”

As a clinician-scientist at the Kingston General Hospital Research Institute, Dr. Berman knows how difficult those decisions can be, especially in his research area of prostate cancer, where at least half of all diagnosed cases are harmless and don’t require treatment. And biopsies – surgical procedures that remove small samples of tumor tissue for analysis – aren’t always effective in distinguishing the harmful cancers from other, relatively harmless types.

“If we could find the biomarkers, or molecular clues, that would tell us which cancers are harmful, we could look for those features in blood or urine tests, and skip biopsies altogether,” he explains. “Blood or urine tests would be faster, less expensive, and less invasive, and ensure that those with the more harmful cancers get their diagnosis and treatment sooner.”

His research is focused on doing just that. A recent recruit to the Queen’s Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine and KGH from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Dr. Berman is leading a team of scientists across Canada who are studying a large number of genes that will form the foundation of new tests for prostate cancer. The group will study prostate cancer samples from two patient groups in Kingston and Montreal, looking for specific molecular features, such as the modification, gain or loss of particular genes.

The goal of this work, funded by Movember and Prostate Cancer Canada, is to develop new and better tests that help clarify decision-making for men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer, and improve their quality of life.

“There are some features for these tests that look really promising,” he says. “We’re hoping to identify tests that will tell us at the time of biopsy whether the patient’s cancer is harmful.”

He’s happy with his progress so far, in part because of some distinct advantages in his research environment in Canada, he says. The first is Cancer Care Ontario’s patient registry, a computerized database that provides researchers with a wealth of scientific data about cancer diagnosis, treatment and outcomes for all Ontario cancer patients. “It’s an advantage of Canada’s single-payer health care system,” he says. “Johns Hopkins didn’t have anything like this.”

He also credits the NCIC Clinical Trials Group, literally next door, in the Queen’s Cancer Research Institute. “Having the clinical trials group on site means we can take research to the next level by doing a patient trial.”

Dr. Berman was one of 14 researchers across Canada jointly awarded a five-year, $5 million Movember Team Grant from Prostate Cancer Canada. The team, called PRONTO, is focusing on rapid development of novel diagnostic markers for early prostate cancer.

This story is the third in a series on the KGH Research Institute and the clinician-scientists recruited to work in the centre.