Going for Baroque

February 12, 2020

Share

Baroque art and style swept Europe and the world between 1580 and 1750, moving onlookers with its emotion, movement, and vitality. Fittingly, a lifetime of support from visionary philanthropist Alfred Bader has elevated the celebrated style even further by championing Baroque art researchers to pursue specialized study at Queen’s University.

•

A passion for Rembrandt

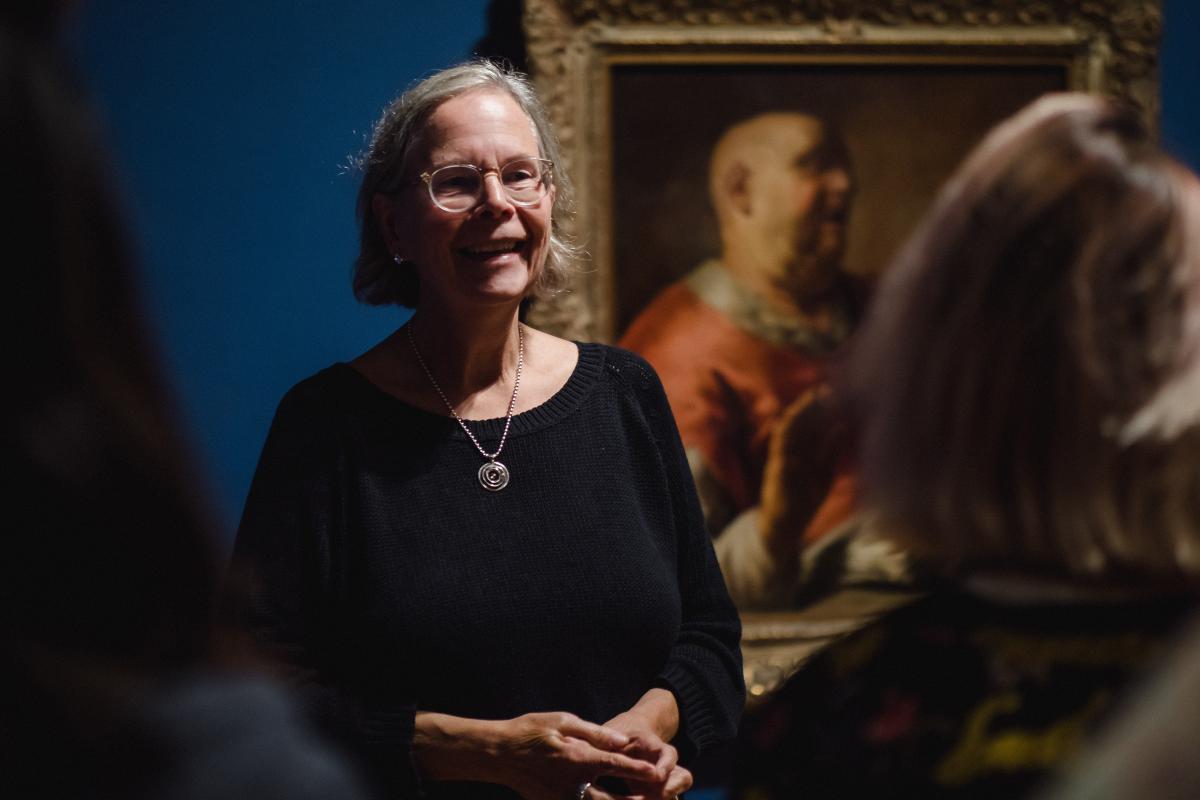

“It was the offer of my dream job,” says Stephanie Dickey, Professor of Art History, reflecting on the moment in 2005 when she was asked to accept the Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art at Queen’s. Dickey was teaching a broad range of courses in art history at Indiana University at the time and leapt at the chance to focus her teaching and research on a period of art for which she held a deep passion – particularly the works of baroque icon, Rembrandt.

“At any museum exhibition, people line up for Rembrandt,” she says. “His work is relatable, expressive, and powerful, capable of representing the most idolized religious figures in the most human way. His depictions of emotion have managed to move viewers for centuries.”

The late Dr. Bader’s passion for Rembrandt and his contemporaries inspired him to work with Queen’s to create the Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art in 1991 to fund scholarly research and teaching. Over the years, he and his wife Isabel entrusted nearly 200 European paintings from their personal collection to the university’s Agnes Etherington Art Centre, including three Rembrandt paintings. Dr. Bader’s son Daniel Bader and his wife Linda later donated a fourth Rembrandt to the Agnes in his honour.

“Alfred was a published art historian as well as a collector, and his enthusiasm and commitment to advancing our understanding of European art, especially the work of Rembrandt and his circle, have supported my work greatly,” says Dickey. “With Bader funding, I’ve been able to convene five international conferences since 2009 that bring the field’s leading experts to the Bader International Study Centre (BISC) at Herstmonceux Castle – I like to think of them as Rembrandt incubators. Discussions that started there have led to groundbreaking publications, interdisciplinary research projects, and global exhibitions. It is especially gratifying to hold these events at the BISC, which was also a gift to Queen’s from Alfred and Isabel Bader.”

Dickey’s sixth conference is slated to take place at the BISC next year, and will reflect on discoveries stemming from exhibitions and events happening worldwide in 2019 to commemorate the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt’s death.

•

Baroque style around the world

Dr. Bader’s interest in Baroque art knew few bounds. In 2002 he worked with Queen’s to create a complementary chair role to explore the impact of the style in Southern Europe and beyond.

Queen’s Professor of Art History, Gauvin Alexander Bailey, came to Queen’s eight years ago as the Bader Chair in Southern Baroque. He cites the role’s support as providing him freedom to think outside the box and stretch his scholarship in new directions.

“Although extremely helpful, major grants are, more often than not, project-specific,” says Bailey, whose study of Baroque art focuses primarily on Italy, South America, the Caribbean and Southeast Asia. “Bader funds, however, have allowed me to widen my scope to explore lesser-known or unexpected avenues as they arise.”

With the assistance of Bader funds, Bailey has published four new books and 29 scholarly articles on global Baroque art, formed fruitful international collaborations, and examined historic sites and artifacts as far away as Bolivia, Ghana, and Suriname. His current projects involve studies of Louis XIV’s embassies to the King of Siam in the 1680s, a French Baroque palace in 18th century India, and the Saigon Opera House.

•

Enhancing education

Together, the Bader Chair appointments in the Department of Art History and Art Conservation are advancing our academic understanding of Baroque art and its influence across the globe. That said, both Dickey and Bailey underscored another area of growth that benefitted significantly from Bader support – the Queen’s student learning experience.

“Best of all, the Baders’ generous support for my research translates into a better learning experience for my undergraduate and graduate students,” says Bailey. “I am able to include fresh research perspectives from archival and field work, and from my international colleagues, as well as up-to-date photographs in my lectures and seminars. Combined with the Bader Collection at the Agnes – where I take my classes often – students have expressed new levels of curiosity and inspiration.”

Dickey expressed similarly: “As I’ve watched many of my former graduate students go on to become accomplished curators and researchers, I continue to gain appreciation for the educational opportunities provided by Bader philanthropy, not only here on campus, but also through fellowship funding that enables our PhD students to conduct original research in Europe and elsewhere around the world.”

Those looking to experience Baroque artworks in person can pay a visit to Queen’s University’s Agnes Etherington Art Centre. Man with Arms Akimbo, an imposing portrait painted by Rembrandt in 1658, is currently on display, while three smaller works by the master are part of an exhibition traveling to art museums in Edmonton, Regina, and Hamilton.

•