THE CONVERSATION

Screenshots have generated new forms of storytelling, from Twitter fan fiction to desktop film

December 9, 2022

Share

Screenshots are as banal as they are ubiquitous. Nowadays, virtually all computer and digital mobile devices can generate a screenshot with a quick pair of key presses. Maybe that’s why they have remained largely underappreciated as a creative practice.

Yet, a closer look at the screenshot tells us interesting stories about not only how media transforms over time, but also how even the humblest technical operation may give rise to sophisticated cultural forms.

Yet, a closer look at the screenshot tells us interesting stories about not only how media transforms over time, but also how even the humblest technical operation may give rise to sophisticated cultural forms.

What began as a simple way to document electronic images has evolved into a form of expression of its own.

Portable form of annotation

Because screenshots are so simple to make, they’re a convenient form of annotation. Over the years, computer media have become increasingly dynamic and abundant to the point of being overwhelming.

Screenshots provide a way for users to deal with this issue by isolating certain elements from the huge volume of data they encounter every day and preserving these elements as self-contained pictures.

Screenshots facilitate recollecting content in visual format. Part of their appeal is to sidestep the exclusivity and ephemerality of social media: for example, when people want to share a social media post with someone who isn’t a user on that platform.

The power of the screenshot comes from this capacity to displace captured information. The screenshot makes things portable.

The possibilities it creates for moving images across distinct channels increase users’ control over this process. More flexibility in how media objects are constituted and circulate leads to a wider variety of ways to archive them and articulate their meanings.

‘Print screen’

In older, text-based operating systems, the command print screen literally sent the screen contents to a connected printer.

Print screen is a tacit reminder that, though it may feel native to digital technologies, the screenshot has a history that precedes them. The need for documenting screen media and representing it in other formats has existed long before personal computers were a thing.

Decades ago, what if a museum needed to document the video art pieces being shown at an exhibition? Or a magazine wanted to demonstrate a new software interface to its readers? Screens had to actually be photographed.

Video game magazines

The method of photographing screens resembles reproduction photography (repro-photography), a professional technique for duplicating unique images like paintings and engravings.

The goal of repro-photography is complete transparency, which entails representing the image as if nothing existed between it and the viewer. It is therefore crucial for the copy to be completely faithful and not betray signs of its origin. In order to achieve this, the capture process must be strictly controlled.

While this may be difficult to do well, with the proper equipment, forms of reproduction photography are accessible even to amateurs.

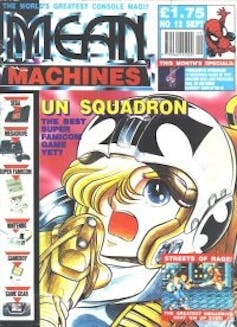

Popular video game magazines from the 1990s invited readers to submit pictures of their screens as evidence of their high scores. These magazines often came with instructions on how to photograph screens.

Richer media format

A lot has changed since the time of those analog screenshots. In its present digital iteration, the screenshot is not only easier to accomplish, but also a richer media format: Screens can now be recorded in full fidelity, and also in video, with accompanying audio or voice-over narration.

The esthetic conventions governing the practice have also changed. There isn’t the same preoccupation about cleaning the screenshot from the “accidents” of its making — including interface components (like a thumbprint) that may indicate the screenshot’s origin.

In fact, the appeal of the screenshot now seems to lie precisely in the presence of those elements. The dislocation they imply adds context to the image and provides it with extra layers of meaning.

Additionally, those elements can be a source of amusement. They emphasize the character of the screenshot as a fortuitous finding amid the banality of everyday media. Whereas the analog screenshot is aimed at the immediacy of reproduction techniques, the digital one calls upon the serendipity of street photography.

Desktop film

The esthetic of digital screenshots has found its way into forms of storytelling both avant-garde and popular. One of the most critically appreciated is the desktop film, a fast-growing genre of audiovisual narratives that unfold entirely in the space of a computer screen.

The first desktop films to become popular were experimental works that were like essays in nature. These used the plasticity of graphic interfaces to explore juxtapositions between media from different sources in a form of expanded montage.

This formula is now also being used in more commercial projects that embrace the screen as the space of the story or incorporate mediation processes as narrative elements in themselves — as often happens in the found footage genre, where the nature of the image carries a particular meaning related to the events that took place.

Social media alternate universe

On a different side of the cultural spectrum, there is a type of fan fiction dubbed social media alternate universe, or smau.

Smaus are fictional narratives created by fan communities in the spirit of old epistolary novels. They are told through the interaction of the characters via fake social media accounts on platforms like Twitter, in posts often rendered and shared as screenshots.

— internet hall of fame (@InternetH0F) October 21, 2022

This format elicits feelings of proximity with the characters, drawing on the allure of the para-social relations that proliferate in social media.

The fact that the dialogues are presented in the same online spaces that the audience regularly inhabits makes them feel more immersed in the story, as if they were eavesdropping on personal conversations.

Beyond documentation

Art forms such as desktop films and smaus illustrate how digital screenshots can do much more than simply document an event.

For many people, screens have become the epicentre of everyday relationships and activities. The computer desktop is our chief working environment.

Instant messaging windows and social media feeds are the main gathering places where we meet one another. The screenshot is as close as we can get to an accurate picture of this world. It can be a privileged way to represent it and participate in its narration.

_____________________________________________________![]()

Gabriel Menotti, Associate professor, Film and Media Department, Queen's University, Ontario

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Conversation is seeking new academic contributors. Researchers wishing to write articles should contact Melinda Knox, Director, Thought Leadership and Strategic Initiatives, at knoxm@queensu.ca.