Queen's University is home to an exceptional collection of outdoor art. It's publicly accessible seven days a week, dawn to dusk and free of charge.

Permanent Art

- Artist: Peter Kolisnyk (Canadian, b. 1934)

- Year: 1978

- Material: Steel

- Purchase information: Purchased with funds from the Chancellor Richardson Memorial Fund and Wintario, 1981

- Location: On the front lawn of Theological Hall

Peter Kolisnyk's minimalist and conceptual sculpture explores the processes of representation and perception. The goal of Ground Outline is to bring our attention to the surrounding environment rather than to the object itself.

This piece was originally installed at Harbourfront in Toronto, where viewers were able to catch a glimpse of Lake Ontario and the surrounding harbour through its frame. Queen's campus was surveyed extensively to find a location that did justice to the sculpture: the sweeping slope in Summerhill park is a dramatic setting. By providing a frame through which one can view the landscape, Ground Outline puts the landscape on stage and heightens awareness of our presence in it.

"The Big White Frame"

By David Missio

This article was published in the Queen's Journal on Tuesday September 9, 2003 (Issue 5, Volume 131)

Art is scary. It is very hard to fully appreciate the intricacies of the art world when your education on the subject matter revolves around Jon Arbuckle scolding Garfield for sending Nermal to Abu Dhabi.

Some of you may scoff at this, holding your heads high, secure in your knowledge of abstract expressionism and postimpressionist fauvism, but how many can confidently stare about campus at the various illogical structures dubbed "works of art" by a select few, and "donut on a pole" or "big white picture frame thing" by others?

Our campus houses a wide variety of highly original outdoor sculptures that have been the subject of confusion or indifference for years, but no longer. Over the next several weeks the Journal's Arts and Entertainment team will be exploring the under-appreciated outdoor sculptures, so that students no longer need refer to them by names like "the big orange triangle with a hole in it." One of the most revered of these sculptures is undoubtedly Ground Outline located on the front lawn of Theological Hall.

Constructed out of steel in 1978 by Canadian artist Peter Kolisnyk who hails from Peterborough, the white rectangular frame was originally installed at Harbourfront in Toronto. Passersby were able to stop and see Lake Ontario and the surrounding harbour through its frame. Ground Outline is a minimalist and conceptual sculpture, meant to bring a spectators attention to the world around them as opposed to the structure itself.

In 1981 Queen's University purchased the sculpture with funds from the Chancellor Richardson Memorial Fund and Wintario. The campus was extensively surveyed in order to find a suitable location that would best represent Kolisnyk's intent. The sloping lawn by Summerhill park proved to be ideal, and Ground Outline was erected much to the confusion of students for years to come.

Kolisnyk meant to put the landscape on stage when he constructed the sculpture, heightening the awareness of nature's presence through a framed perspective. Through its inherent simplicity, Ground Outline is undoubtedly one of the easiest of the outdoor sculptures to understand and appreciate.

- Artist: Jordi Bonet (Canadian, b. 1932, Spain - 1979)

- Year: 1972/73

- Material: Aluminum

- Purchase information: Commissioned by the Art Purchase Committee for Duncan McArthur Hall, 1972

- Location: In front of the south entrance to Duncan McArthur Hall

Jordi Bonet was born in Barcelona and moved to Quebec in 1954. He is known for large ceramic murals, in which rustic, sometimes representational imagery similar to that used in Iron Man is deployed.

This work was commissioned on the completion of Duncan McArthur Hall and was made specifically for this location.

In Iron Man, Bonet attempts to reconcile twelfth-century Romanesque and twentieth-century Cubist aesthetics. The triangle patterns decorating the smooth surfaces at the top of the sculpture are reminiscent of Picasso's use of similar motifs, while other textures suggest the rustication on Romanesque sculpture and fortifications. As well, the proportions of the work recall the massive, upright figurative sculptures of the Romanesque period. The result is a decorative combination of modern and medieval sensibilities.

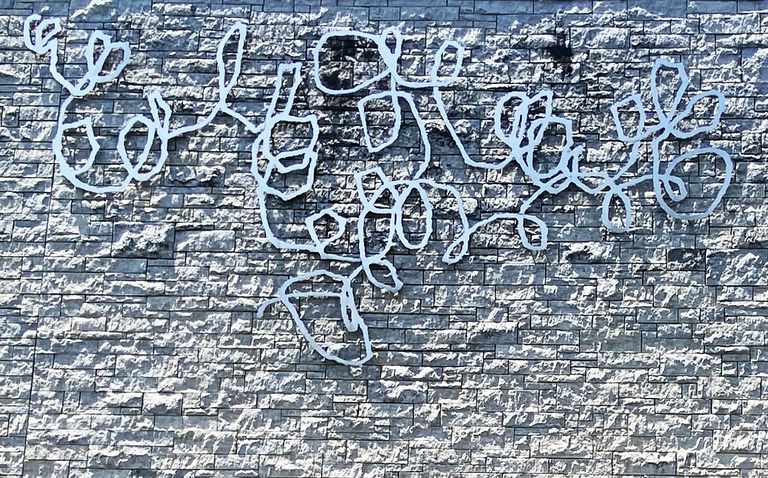

- Artist: Micah Lexier (Canadian, b. 1960)

- Year: 1999

- Material: Water-jet cut stainless steel

- Purchase information: Commissioned with the support of the Millennium Arts Fund of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Chancellor Richardson Memorial Fund and Thyssen Marathon Canada Limited, 1999

- Location: East wall of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre

The New York-based conceptual artist Micah Lexier explores the themes of identity and time in A Minute of My Time, a monumental piece commissioned to mark the passing of the millennium.

It belongs to a continuing series of works begun in 1995, based on automatic drawings completed in one-minute periods of time.

The drawing on which this sculpture is based was created by Lexier the day he first visited the site. As such, the drawing - rendered in steel - is a record of the artist's presence in Kingston at that time.

The piece is a playful graphic expression of the preciousness of each passing moment. It adorns the new facade of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, which reopened in May 2000.

"The Squiggle on the Wall"

By Catherine Hale

This article was published in the Queen's Journal on Tuesday September 23, 2003 (Issue 9, Volume 131)

For this week's instalment of understanding outdoor sculpture on campus, I decided to undertake some in-depth field research. I wanted to find out just what kind of ideas have been floating around about the 'squiggle on the wall.'

The first thing I discovered was that many people have never noticed the shiny metal sculpture mounted on the east wall of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre. This may be because traditionally we expect sculpture to be presented at ground level, or raised on a pedestal or platform to draw attention to it.

Those who had noticed 'the squiggle on the wall' had a wide variety of interpretations of the piece. A recurring thought was that the squiggle is a stylized rendering of the name of the art centre. Another suggestion was that the squiggle is a map of some kind. Who had the right idea? Um, well, no one.

What we fondly refer to as 'the squiggle on the wall' is actually just that: a squiggle, a doodle, a free-hand drawing. The title of the work is A Minute of My Time (September 29, 1998 15:04-15:05) and it is part of a series of automatic drawings or doodles produced by Micah Lexier in one minute.

A Canadian artist, Lexier was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba in 1960. He received his BFA from the University of Manitoba in 1982 and his MFA from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in 1984. He currently resides in New York.

A Minute of My Time was initially created by Lexier on a train leaving Kingston after visiting the Art Centre site. The drawing was then enlarged through a computer scan. The stainless steel used in the sculpture was water-jet cut using a computer-guided process. The enlargement of the initial doodle is apparent when looking closely at the sculpture. The edges of the steel are not smooth ? you can see the rippled edges where ink would have bled on the original paper.

Through this work, Lexier explores the passing of time. The doodle is a graphic representation of a minute spent in the mindless act of doodling.. Usually, public monuments are expected to commemorate a historical event, person, or ideal. By presenting the drawing on a monumental scale, the artist captures and freezes a fleeting moment in his life, bringing attention to its importance.

Our preoccupation with time and its measurement came to a climax with the anticipation of the new millennium. To mark this momentous event, A Minute of My Time was commissioned with the support of the Millennium Arts Fund of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Chancellor Richardson Memorial Fund and Thyssen Marathon Canada Ltd.

Next time you look down at your class notes and see the countless scribbles in the margins of the pages, perhaps you will stop and consider just how many precious moments you have captured.

- Artist: Raymond Spiers (Canadian, b. 1934)

- Year: 1972/73

- Material: Fibreglass over foam core

- Purchase information: Commissioned by the Art Purchase Committee for Duncan McArthur Hall, 1972

- Location: In the north courtyard of Duncan McArthur Hall

Bent Yellow is one in a series of works in which Raymond Spiers attempts to share the creative experience of artists with viewers.

Spiers made small hand-held model sculptures, or modules, by joining simple moveable forms together in a way that allowed a variety of arrangements to be created by the viewer/participant.

The Dean's Committee for Art Purchases had the opportunity to touch and move a smaller replica of the modules and select the final arrangement of the current sculpture.

Bent Yellow is an enlarged replica of that arrangement, although, by necessity, the units of the full-scale piece are not moveable. The work is typical of the 1970s in its attempt to demystify and engage others in the processes of artistic creation. Also, many artists explored the use of fibreglass in this period: a new material at the time, fibreglass was seen as a strong, lightweight medium well suited to modernist aesthetics.

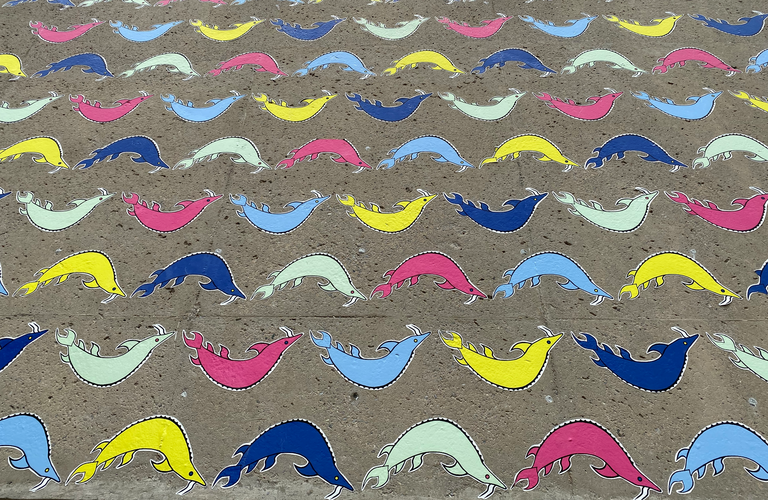

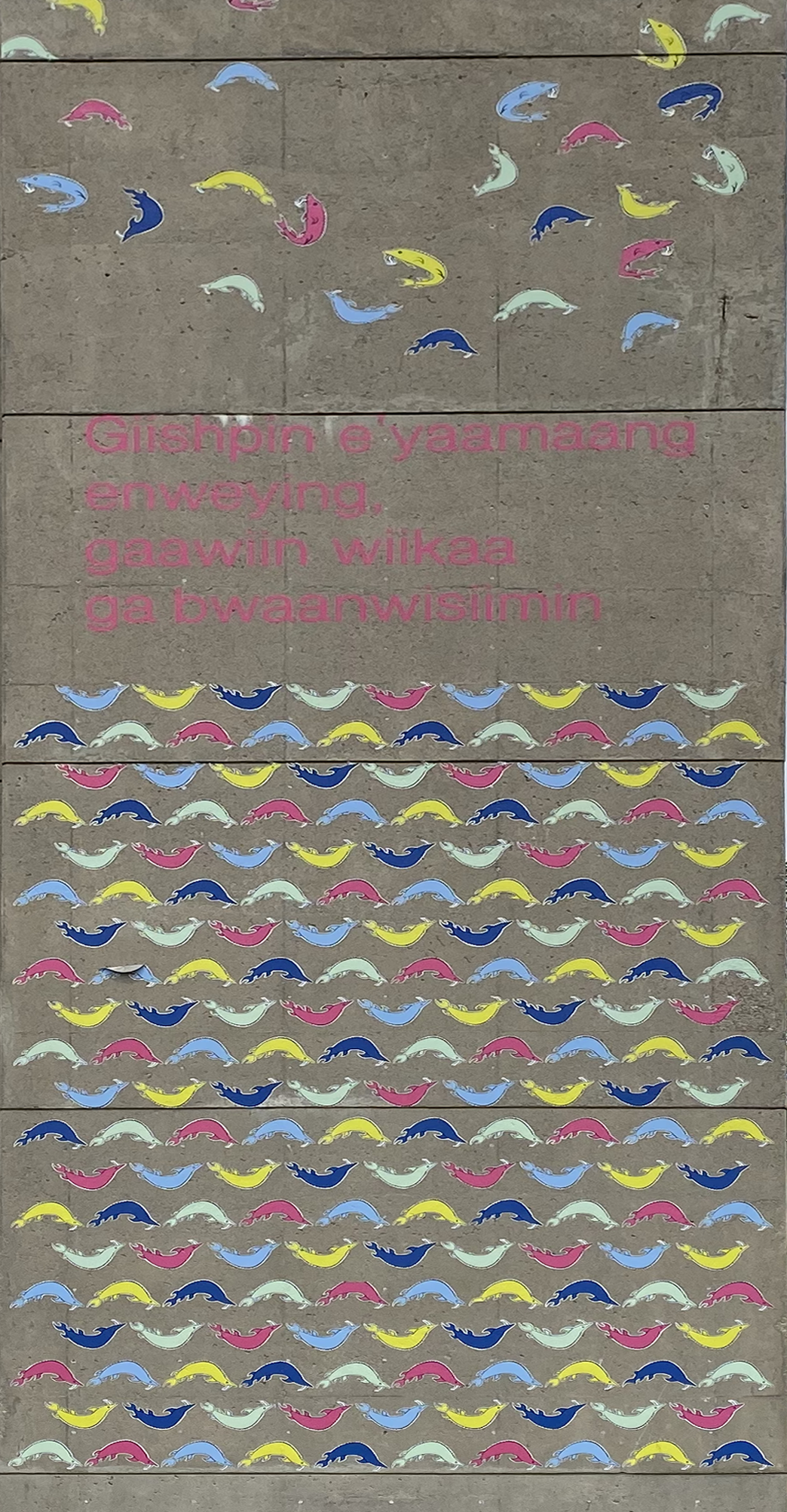

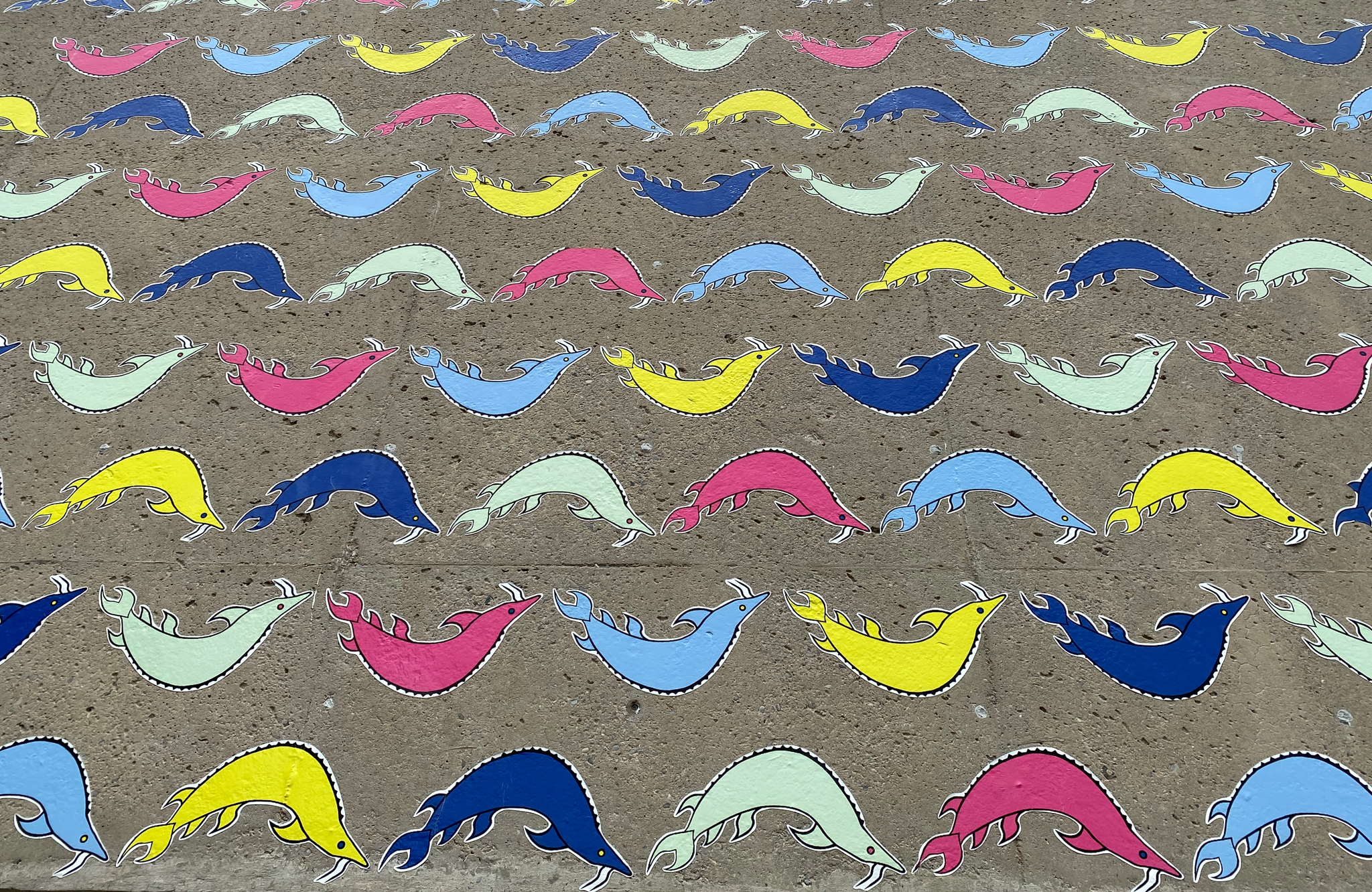

- Artist: Ogimaa Mikana - Susan Blight (Anishinaabe, Couchiching, b.1977); Hayden King (Anishinaabe, Gchi'mnissing, b.1980

- Year: 2018

- Material: Vinyl Transfer

- Purchase Information: Chancellor Richardson Memorial Fund, 2019

- Location: South façade of Mackintosh-Corry Hall

Never Stuck is a direct response to a Facebook post by Niizhoosake Sherry Copenace: “As Anishinaabe we have been given our way of life to solve and get through any situation. Anishinaabe is not ever stuck.” This profound articulation of Anishinaabeg resistance and adaptation is reflected in the repeated sturgeon imagery. Respected by Anishinaabe, the fish have suffered under colonial overfishing and damming, but are now returning to ancestral waters in greater numbers. Just as sturgeon persevere, the Anishinaabeg are never stuck.

- Artist: Victor Tolgesy (Canadian, b. 1928, Hungary - 1980)

- Year: 1971

- Material: Steel

- Purchase information: Commissioned by the Department of Mathematics and Statistics, 1971

- Location: On the plaza west of Jeffery Hall

Victor Tolgesy was born in Hungary and emigrated to Canada in 1951.

Sakkarah was commissioned by the Department of Mathematics for the sunken courtyard on the east side of Jeffery Hall. For this site, where the sculpture would typically be seen from above, Tolgesy chose to work with a pyramidal structure as it would not suffer perspectival distortion when viewed from a height.

Sakkarah, a purely formalist sculpture, is about the intersection of two forms: the sphere and the pyramid. The artist's self-imposed restraint of visual motifs creates a lyrical quality where one shape responds to the other in a visual rhythm. When repairs were made to the courtyard, the sculpture was moved to its present location.

"The Big Orange Triangle"

By Catherine Hale

This article was published in the Queen's Journal on Tuesday September 30, 2003 (Issue 11, Volume 131)

When confronted by "the big orange triangle" on your trips across campus, it is important to note that its current location, on the plaza west of Jeffery Hall, is not the location for which it was intended. The sculpture was actually designed for the sunken courtyard on the east side of Jeffery Hall, but was removed in 1998 when the area needed repairs.

Why is the location important? What we refer to as "the big orange triangle" is a sculpture that embodies the intersection of two forms; the pyramid and the sphere. The use of the pyramidal shape was a particular choice made by the artist because it does not suffer distortion when viewed from above. This way, the viewer could enjoy the sculpture from ground level or from the benches looking down on it.

One interpretation of "the big orange triangle" is that it is a purely formalist sculpture. Formalism is a theory of art that emphasizes the form or structural qualities of a work over its content or context. According to this theory, the most important aspect of a piece is the way that it organizes the elements of art using the principles of design. When this sculpture was commissioned in 1971, formalism was considered one of the most powerful critical approaches. When analyzed with respect to formalism, "the big orange triangle" can be appreciated for the way that the pyramid and sphere forms respond to each other, creating a visual rhythm.

Not satisfied? For those of you who crave content and context in your understanding of art, don't worry, there is another interpretation.

The actual title of "the big orange triangle" is Pyramidal Structure - Sakkarah, and it was designed by Victory Tolgesy, a Hungarian-born Canadian artist who passed away in 1980. An alternative interpretation of this work requires that we pay specific attention to the second half of the title. The first part, "Pyramidal Structure" can easily imply a formalist interpretation, but what is "Sakkarah?"

As it turns out, Sakkarah is the name of the site in Egypt on which the first monumental tomb, or pyramid, was built. It has been suggested that Pyramidal Structure - Sakkarah is representative of peace. The most obvious reason for this symbolism is the fact that Sakkarah was to serve as the royal cemetery for the Old Kingdom. Further reasoning for this connection is the idea that in order to build the pyramids, Egypt had to be at peace with its closest neighbours. Because the building of the pyramids required massive manpower, workers from across the land united to accomplish this great task. Through the creation of the pyramids, the provinces joined together to form the world's first nation-state.

Then why the inclusion of the sphere? It might be intended to reinforce notions of unity, completeness and integrity that are central to the building of the pyramids and the achievement of peace.

Regardless of which interpretation you prefer, there is a direct link to the folks at the department of mathematics and statistics who were responsible for commissioning Pyramidal Structure - Sakkarah. As a purely formalist sculpture, the work explores geometric shapes. As a symbol of peace, the sculpture recalls the building of the pyramids, which relied on a sophisticated understanding of mathematical concepts.

Is the recipe for peace rooted in mathematical equations, or should we simply enjoy the aesthetic qualities of geometric forms? I'll let you be the judge.

- Artist: Henry Saxe (Canadian, b. 1937)

- Year: 1979

- Material: Steel

- Purchase information: Purchased with Canada Council and Gallery Association matching funds, 1982

- Location: Located on the lawn south of Harrison-LeCaine Hall

Henry Saxe, who works north of Kingston in Tamworth, has an interest in process-driven working methods: frequently, scrap materials that are suggestive of a larger concept are his source of inspiration.

Although Saxe's work is usually orderly and systematic, the arrangement of steel plates in Thataway Again has an incidental quality. This sense of folding or breakdown, combined with the use of industrial materials, gives the sculpture great vitality.

Thataway Again emerged from a series of works created by Saxe in the late 1970s and early 1980s, some of which were exhibited at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in 1983.

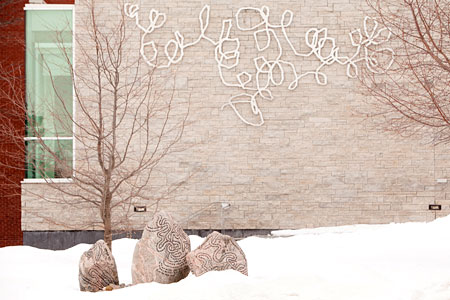

- Artist: William Vazan (Canadian, b.1933)

- Year: 1992

- Material: Sand blasted granite

- Purchase information: Gift of Dr. Michel D'Avirro, 1992

- Location: North-East Lawn of Miller Hall, at the corner of Union St. and Arch St.

As a land artist working during the 1960s and 1970s, William Vazan made conceptual works that articulated the intimate relationship between humankind and the earth.

In the late 1980s, Vazan began to rout granite stones in a quarry north of Kingston near Tamworth. He uses a sand blaster to draw on the stones in a process that he describes as an intuitive expression of the aura and character of each stone. The engravings, suggestive of imagery from ancient civilizations, are interpretations of universal archetypes.

In The Three Observed, the kinetic lines crossing the surface seem at odds with the immense size and weight of the boulders, creating an unusual quality of frantic energy inhibited by paralysis. Vazan's work fuses natural form with imagery borrowed from ancient traditions to suggest a unifying energy permeating matter and human culture.

"Big Weird Rocks"

By Catherine Hale

This article was published in the Queen's Journal on Tuesday October 21, 2003 (Issue 16, Volume 131)

As you go about your daily business, traveling from here to there and doing this and that, how many times have you come across a rock? Large or small, rough or smooth, round or jagged. Maybe you sat on it to eat your lunch, moved it aside to make room for something else, or maybe, just maybe, you gave it a little kick.

On any of these occasions, did you stop and think about that rock? I mean really think about it. How old is it? Where did it come from? Where will it end up? It's easy to forget that rocks were here long before we were, and will likely remain long after we are gone. The rock that sits in the gutter on University Avenue has been witness to events that the human mind cannot even fathom.

Perhaps the stones scattered around the streets of Kingston haven't caught your attention, but in your travels past the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, you may have noticed the three large rocks that make their home on the front lawn. Fondly referred to as "big weird rocks," these stones were designed to draw the viewer's attention to their history, and in turn, the history of the universe.

For years, geologists have been using our silent friends to provide insight into the origins and history of the universe. In The Three Observed (1992) Canadian artist William Vazan encourages the viewer to consider this very notion. Unlike other sculptors, who use their material only as a vehicle to depict a subject, the rock itself is central to the meaning of Vazan's work.

Using a sandblaster, the artist marked the surface of the granite with a series of patterns, signs and symbols reminiscent of archaic times. He did not work against the rocks, but rather, he worked with them, giving the granite a voice through his energetic design. The surface directs the viewer's thoughts to the beginnings of humanity, and inevitably, to the history of the rocks and the universe itself. In this sense, the rocks become symbolic tools with which the audience is able to travel back through time to places and events that are only comprehensible in the realm of the imagination.

Vazan promotes open interpretation. He encourages us to create our own myth about the origin of the universe, merging real and imaginary worlds. This merging is reinforced by the inclusion of "wormholes" in the rock's surface. A relatively recent scientific phenomenon, the "wormhole" is a sort of shortcut through spacetime which makes different parts of the same spacetime closer than usual. By including these symbols in the rock's surface, Vazan suggests that the viewer is able to access the past through the use of the imagination in the present.

Another facet of the sculpture which adds to its experiential nature is its extremely tactile appearance. You can't help but want to touch it. This plays into the viewer's experience of the work in terms of its truth value. As humans, we have a tendency to want to be able to touch things to know they are real. The act of touching reinforces our connection with the rock and in turn with its history and meaning.

The relationship between the human and the natural world is a theme that runs throughout Vazan's work. He seeks to awaken our ecological conscience, and remind us of our connection to the natural order of the universe.

Vazan's emphasis on the relationship between humanity and nature is especially appealing because of its universality. The Three Observed provides no distinct interpretation of the origin of the universe, but rather encourages the individual to create their own myth and evaluate their relationship with the natural world.

Vazan's works can be found in many Canadian cities as well as Korea, Japan and France. The installation on the lawn on the Agnes Etherington Art Centre was a gift from the private collector Dr. Michel D'Avirro in 1992.

Perhaps the next time one of our silent friends crosses your path, you might stop and consider the vast experiences it has witnessed, therein giving the rock a voice through the boundless realm of your imagination.

- Artist: Camille Georgeson-Usher (Coast Salish-Sahtu Dene-Scottish, b.1990)

- Year: 2018

- Material: Vinyl Transfer

- Purchase Information: Chancellor Richardson Memorial Fund, 2019

- Location: West façade of Agnes Etherington Art Centre

through, in between oceans disrupts concrete walls with colourful, abstracted representations of beadwork, land and water, which enfold and fill the spaces in between portraits of the artist and her paternal grandmother. This site-specific intervention asks how Indigenous peoples can make subtle gestures to recognize each other’s bodies, while navigating through often unsafe urban territories. These gestures aren’t always bold; they can be the everyday gestures of people looking for a part of themselves in what the artist calls the “spaces in between.”

- Artist: Kosso Eloul (Mourom, Russia 1920–Toronto ON 1995)

- Year: 1971

- Material: stainless steel

- Purchase information: Gift of Rita Letendre, 2005

- Location: Exterior front entrance to Leggett Hall

- Artist: Tehanenia’kwè:tarons (David R. Maracle)

- Year: 2022

- Material: Concrete

- Location: Albert Street Residence (Endaayaan – Tkanónsote) Courtyard

The fabrication process for the gathering space involved reproducing a Two Row Wampum Belt through 3D scanning and printing for the backs of the benches. The original bench, made of reclaimed building materials from Queen’s, was molded using RTV rubber, and three lightweight concrete casts were produced. The turtle shell was created digitally, molds were taken from this pattern and then cast from lightweight concrete.

The Tékeni Teyohá:te Káhswentha (Two Row Wampum Belt) records the first agreement between the Haudenosaunee and the Dutch, with oral histories dating back to 1613. The belt defines a mutual agreement between the Haudenosaunee and European settlers to live in peace while pursuing parallel, but separate paths of culture, belief, and law. The two dark rows on the belt symbolize a canoe and a ship floating side by side on the river of life. The vessels are bound together by a symbolic three-link chain, these being the light colour rows on the belt, representing Friendship, Good Minds, and Peace.

The Turtle shell installed represents our Mother Earth; that we walk softly on her, on the back of the great turtle during our time here. The benches represent our oldest ancestors, while the Two Row Wampum Treaty belts that wrap around them are representative of the Haudenosaunee way of life, that we respect each other in all of our differences; that we do not impose our laws, cultures, and ways on each other.

The incorporation of an Indigenous gathering space into the newly opened student residence building is one facet of the university’s wide-ranging effort to decolonize and Indigenize campus life.

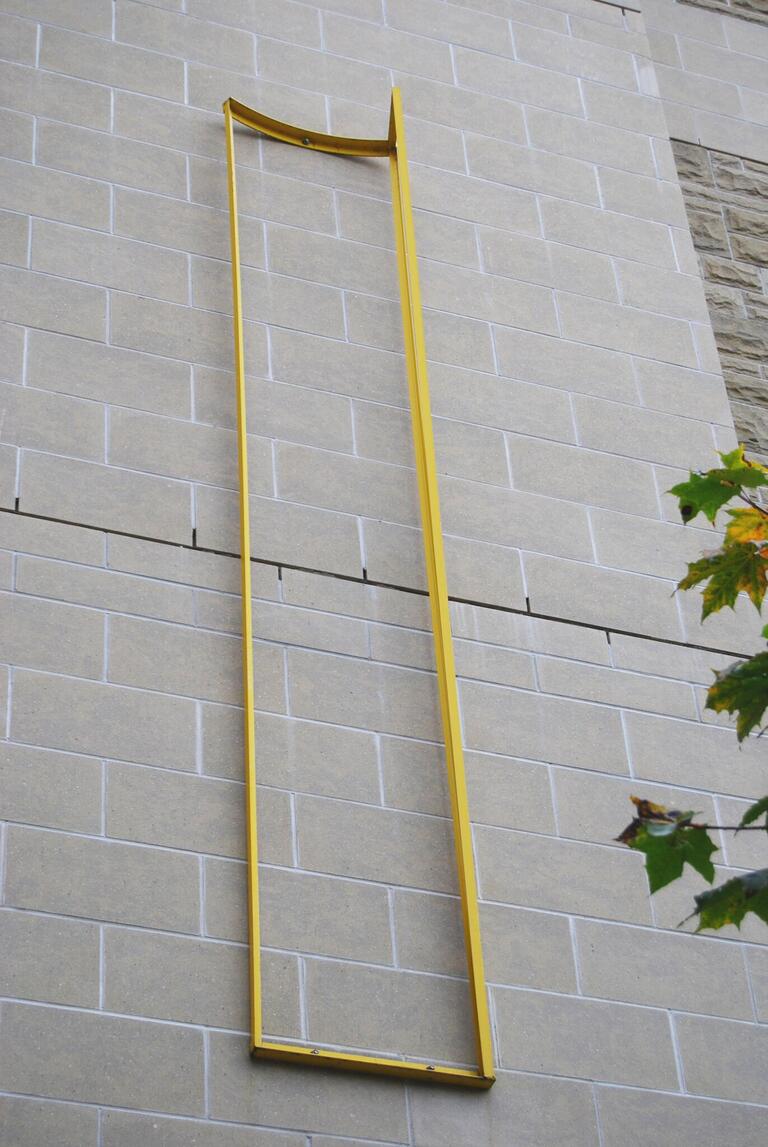

- Artist: André Fauteux (Canadian, b. 1946)

- Year: 1973

- Material: Steel

- Purchase information: Donated by Gesta Abols, 1985

- Location: On the northeast wall of the Biosciences Complex

On the occasion of André Fauteux's ten-year retrospective at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in 1982, curator Karen Wilkin described his work as "a continuing conflict between a Platonic sense of the ideal and a modernist appreciation of the unpredictable."

This tension is evident in Fauteux's Untitled. The artist's customary sculptural materials, slender beams of steel, are assembled to produce the long central rectangle. At first glance, the sculpture appears symmetrical. However, the slight curvature along the width of the sculpture and the short arm protruding on the right reveal that it is not. This subtle and elegant form hovers between the ideal and the deviant.

"The Biosci Box"

By Catherine Hale

This article was published in the Queen's Journal on Friday, November 7, 2003 (Issue 20, Volume 131)

Last, and perhaps least, our Understanding Outdoor Sculpture series comes to a close with the 'BioSci box.'

This steel sculpture, which is located on the northeast wall of the Biosciences Complex, is an example of minimalist art.

Minimalism refers to a twentieth-century art movement that favoured the reduction of art to the least number of colours, values, shapes, lines and textures. These works are not intended to represent or symbolize any other object or experience.

Untitled was created by Canadian artist André Fauteux in 1973 and was donated to the Agnes Etherington Art Centre by Gesta Abols in 1985. The sculpture first appears to the viewer as a symmetrical rectangle, but upon closer inspection it becomes clear that in fact, it is not symmetrical at all. Along the width of the rectangle there is a subtle curve, and on the right side a short arm protrudes.

Fauteux plays with our expectations of geometric shapes. Because we are so familiar with particular shapes we tend to anticipate the entire form before closely examining it. An illustration of this point would be the way we perceive a sculpture of the human body. When we see it from the front, we already have a specific set of assumptions about what to expect as we make our way around it. If we came to the rear of the sculpture to find a television set where the back of the head ought to be, we would probably be somewhat shocked. Similarly, when looking closely at Untitled, we are surprised to find that the character of the rectangle is not at all what we expected - it isn't symmetrical.

Karen Wilkin, a curator at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in 1982, suggested that Fauteux's work expresses 'a continuing conflict between a Platonic sense of the ideal and a modernist appreciation of the unpredictable.'

How do we determine the aesthetic value of a work that is not intended to represent a particular object or experience? Well, we might take our cue from the artist himself. In a 1977 interview, Fauteux explained that he decides whether or not he likes a piece by 'looking at it and measuring the experience that [he] gets from it.' He asks himself whether the experience was ordinary, boring, or exceptional, and compares it to the experience of other sculptures. If his work provides an exceptional experience relative to other sculptures, then he has succeeded.

Is Fauteux's Untitled a success? With six segments of Understanding Outdoor Sculpture on Campus behind you, hold your head high and march confidently to the Biosciences building where you can make the decision for yourself.

Temporary Art

- Artist: Niki Boytchuk-Hale

- Year: 2021

- Material: Vinyl Transfer

- Purchase information: Queen's University Human Rights & Equity Office, Queen's Consensual Humans Club, and the Alma Mater Society

- Location: Front facade of Harrison-LeCaine Hall

A Love that Clings highlights some of the many ways we can show up with consent in mind for our community and ourselves. A necessary step is acknowledging the range of lived experiences, specifically for Indigenous, Black and People of Colour, 2SLGTBQQIA folks, the disabled community, and women.

The idea of bringing a consent-themed mural to campus was initiated by Queen’s Consensual Humans, a student club founded in 2017 to promote the importance of consent in all areas of campus culture. It was designed by Queen’s fine arts student Niki Boytchuk-Hale.

For her design, Boytchuk-Hale aimed to capture a multitude of perspectives and lived experiences. The mural features dots throughout, which serve as a symbol for the statistic that 1 in 4 North American women will be sexually assaulted during their lifetime. A red ribbon skirt acts as a reminder of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and 2SLGBTQQIA+ peoples, while the dove represents profound peace. The honeysuckle is used across cultures to represent bonds of love; a love that clings without harming anyone.

- Artist: Oriah Scott, EronOne, HONE, HUNGR, AJ Little, Emily May Rose and guest graffiti artists

- Year: 2022

- Material: Spray-paint

- Purchase information: Funded by the Stonecroft Foundation and the City of Kingston Arts Fund, Kingston Arts Council.

- Location: South and west facades of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre

Created by Oriah Scott, EronOne, HONE, HUNGR, AJ Little, Emily May Rose and guest graffiti artists from across the Montreal-Toronto corridor as Agnes’s Stonecroft Foundation Artist(s)-in-Residence.

Enveloping the south and west facades of the Agnes, this large-scale mural was created in the summer of 2022. The artwork features independent pieces from each artist that when placed alongside each other, form a collaborative statement which celebrates the long vernacular tradition of street art in Kingston, points to alternative art histories embedded in our city streets, and provides a framework for experiential learning and co-curriculum development conceived in collaboration with faculty and students from Queen’s Art Conservation Program.

Graffiti as an art form has been omitted from the widely accepted artistic canon and remains an underrepresented art form within galleries and collections — it is an art form mainly occupying public spaces, causing it to struggle finding a home in art galleries. The significance of the piece is to showcase graffiti and aerosol art in Kingston to a broader audience, while highlighting a level of skill and precision that is often overlooked in the art world.

Transformations remains until the construction for Agnes Reimagined begins in summer 2024.

Content of this Outdoor Campus Art Tour section is © Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 2002.

Find us

Find us